God and Cosmic Order

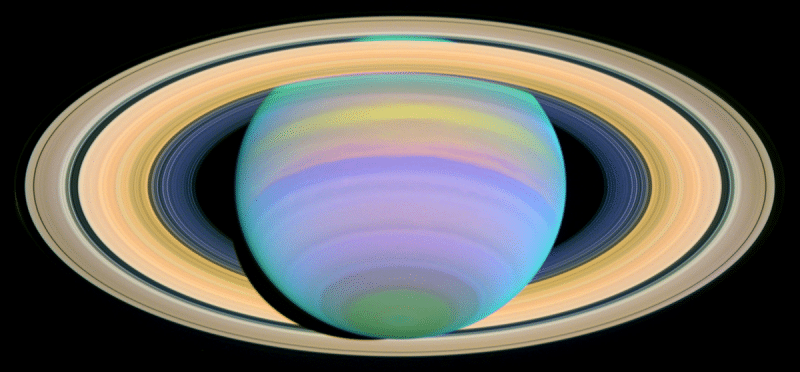

(The NASA picture above is of Saturn taken in ultraviolet light.)

Many atheists regard belief in God as completely irrational, because they think it is not based on any evidence. Richard Dawkins, for example, thinks there is no more evidence for God than there is for “flying spaghetti monsters.”

What leads people to such conclusions, I think, is that they are looking for the same kind of evidence for God that we have for physical things. Physical things can be directly observed with our senses or else inferred to exist as natural causes of the things that we do observe. For instance, we directlly see a compass needle and we infer that there exists some unseen physical thing that causes it to move, which we call a magnetic field. But God cannot be “evident” in either of these ways. He is not a physical thing, and so, obviously, cannot be sensed; and he is not a part of the universe acting as a physical cause upon other parts.

And yet, according to St. Paul, God’s existence is nevertheless evident to us through the things he has created:

“For what can be known about God is plain to them [i.e. “pagans”], because God has shown it to them. Ever since the creation of the world his eternal power and divine nature, invisible though they are, have been understood and seen through the things he has made. So they are without excuse.” 1

The “things he has made” include ourselves and the physical universe; and Christian tradition tells us that both of these creations of God manifest him and allow us to find him. In the words of the Catechism of the Catholic Church,

“[T]he person who seeks God discovers certain ways of coming to know him. … These ways of approaching God from creation have a twofold point of departure: the physical world, and the human person.” 2

The human person, being rational and free, is made in the “image of God.” Through his conscience he hears the voice of God; and in his orientation towards and capacity to know truth, goodness, and beauty “he discerns signs of his spiritual soul,” which “can have its origin only in God.” 3

According to Christian tradition, the physical universe points to God mainly in two ways. The first is by the very fact that it exists. The universe did not have to exist, and yet it does. Why? Why not no universe? Why not no matter, no forces, no laws, no space, no time, just blank non-existence? As Leibniz famously asked, “why is there something rather than nothing?” 4 Natural science, by its very nature, does not provide an answer. It explains the relationships among things that exist, but not why there is anything at all. The answer that Christians and other theists give is that God, who is the fullness of Being, is the source of the being of everything else.

The second way that the physical universe points to God is by the fact that it is orderly. One can call this the “Argument from Cosmic Order.” If one looks at the writings of early Christian thinkers, one is struck by how important a place they give to this argument, and how frequently and consistently they appeal to it. The following quotations5 illustrate their thinking.

- “There exists but one God … He is the Father, God, the Creator, the Author, the giver of order.” (St. Irenaeus, ca. 200 AD)

- “If upon entering some home you saw that everything there was well-tended, neat, and decorative, you would believe that some master was in charge of it, and that he was himself much superior to those good things. So too in the home of this world, when you see providence, order, and law in the heavens and on earth, believe that there is a Lord and Author of the universe, more beautiful than the stars themselves and the various parts of the whole world.” (Minucius Felix, ca. 200 AD)

- “… when we … see … the excellent orderliness of the world, then we worship its Maker as the one Author of one effect, which — since it is entirely in harmony with itself — cannot, therefore, have been the work of many makers.” (Origen, ca. 250 AD)

- “There is no one so uncivilized nor of such barbarous manners that he does not, when he raises his eyes to heaven, … understand something from the very magnitude of things, their motion, arrangement, constancy, beauty and proportion, and that this could not possibly be if it were not established in wonderful order, having been fashioned on some greater design.” (Lactantius, ca. 300 AD)

- “… creation, as if in written characters and by means of its order and harmony, declares in a loud voice its own Master and Creator.” (St. Athanasius, mid 4th century)

- “God, by his own Word, gave to creation such order as is found therein, so that though he is by nature invisible, men might be able to know him through his works.” (St. Athanasius)

- “Let us [even] suppose that the existence of the world is spontaneous. To what will you ascribe its order?” (St. Gregory of Nazianz, late 4th century)

- “… all creation — and above all, as the Scripture says, the orderly arrangement of the heavens — demonstrates the wisdom of the Creator through the skill displayed in his works.” (St. Gregory of Nyssa, late 4th century)

- “… from the origination of the world [and] from its order and beauty … we can recognize that the wisdom and power of him who created [it] and brought [it] into existence far surpasses every [created] mind.” (St Cyril of Alexandria, mid 5th century)

The Argument from Cosmic Order would likely be dismissed by most modern atheists for two reasons. First, many of them would interpret it as saying something rather crude and simplistic. In particular, they might suppose it to be saying that any orderly pattern of physical objects must be the result of someone arranging them “by hand,” so to speak. But we know of countless examples of orderly patterns of objects arising spontaneously through natural processes. For example, the patterns formed by atoms and molecules in crystals do not come from someone deliberately placing them in rows as a bricklayer lays bricks. They arise automatically through the operation of blind and unconscious physical forces.

The crude notion of God arranging things by special “interventions” in the world was quite popular in the 17th and 18th centuries and into the 19th. Isaac Newton himself invoked it to explain the orderly structure of the solar system. He could not imagine how such a structure could have arisen naturally, and he believed that it would be destabilized over time by the mutual gravitational pull of the planets and would therefore need periodic interventions by God to readjust it. A century after Newton, however, the great physicist and mathematician Pierre-Simon Laplace, by using the very laws of mechanics and gravity that Newton had discovered, showed that the solar system is stable and requires no readjustments. Moreover, he showed how the same Newtonian laws can fashion a swirling cloud of dust and gas into structures like the solar system.

The traditional Argument from Cosmic Order, however, is not about God arranging things “by hand.” Taken literally, of course, that notion would be absurd to Christians, as God is not physical and has no “hands.” But even if it is meant as a metaphor for God “intervening” in nature to arrange things, it does not represent the traditional Christian understanding, which is that nature in itself exhibits order. That is, God created nature as orderly and does not have to disrupt or violate the integrity of nature to make it so.

A second response that atheists would make to the Argument from Cosmic Order is that the order in nature is adequately explained by the laws of physics. In fact, we already saw two examples of this in the way that crystals form and the way the solar system formed. However, this response overlooks a very basic point, which is that the laws of physics are themselves instances of order no less than are the various patterns of objects that they explain.

Take, for instance, Newton’s law of gravity. This is an equation that relates the gravitational force between two bodies to the distance between them. If one were to plot on a two-dimensional graph all the possible values of force and distance, one would find that the resulting points all lie on a particular, simple curve. That is, these points have a specific pattern. Admittedly, this is order at a more abstract level than the visible patterns of the planets in space, but it is order nonetheless. In fact, it is an order that is more impressive in a number of ways.

In the first place, the patterns one sees in the planets’ positions are somewhat imperfect. To take just one example, the planets all orbit the sun in the same plane, but they do not do so exactly; their orbital planes are actually slightly askew with respect to each other. By contrast, Newton’s laws of mechanics and gravity are patterns that hold with extreme precision. More importantly, the visible patterns of the solar system apply only to that particular system, whereas the more abstract pattern that is described by Newton’s law of gravity holds throughout the entire universe, from apples falling from trees to the great whirling motions of galaxies.

It is true that we now know that Newton’s laws of gravity and mechanics are not quite exact. They are approximations to laws discovered by Einstein. But Einstein’s theory of special relativity and his theory of gravity describe an order that is even more wonderful and profound than that found by Newton. Einstein discovered hitherto unsuspected mathematical structure in space and time whose rich implications are still being explored a hundred years later. Nor are Einstein’s theories the last word. Most experts believe that his theory of gravity is an approximation to a yet deeper theory of far more intricate structure, most likely what is called “superstring theory.”

As one goes to deeper and deeper levels of the world’s structure — from the patterns of planetary motion that were discovered by Kepler four hundred years ago, down to Newton’s laws, down further to Einstein’s theory of gravity, and down further still to superstring theory — one sees order of increasing intricacy that requires for its description mathematical concepts of increasing subtlety and sophistication. Kepler’s laws of planetary motion involve only some fairly simple geometry and algebra. Formulating Newton’s laws, however, requires calculus. Formulating Einstein’s theory of gravity requires the geometry of curved, four-dimensional, non-Euclidean space-time, including some tensor analysis and differential geometry. The mathematics of superstring theory is so deep and difficult that after fifty years of intensive study, mathematicians and physicists feel that they have barely scratched its surface.

If the progress of theoretical physics has shown us anything, it is that the orderliness of the cosmos is far deeper than anyone ever suspected. Already in 1932, the great mathematician and mathematical physicist Hermann Weyl wrote that “in our knowledge of physical nature, we have penetrated so far that we can obtain a glimpse of the flawless harmony that is in conformity with sublime reason.” 6 In the many decades since, fundamental physicists have penetrated even deeper and obtained much more than a glimpse of that harmony. Several years ago, Edward Witten, regarded by many as the greatest theoretical physicist of his generation, who describes himself as a “skeptical agnostic” in matters of religion, said the following.

“The laws of nature as they’ve been uncovered in the last few centuries, and especially … the last century, are very surprising. … They have a great beauty, which is a little hard to describe, maybe, if one hasn’t experienced it. … They … involve very interesting and subtle concepts. … It is a rich story.” 7

The astrophysicist Avraham Loeb of Harvard, an atheist, was asked in a recent interview whether he was religious. He replied,

“I was secular to start with. I am not religious. I am struck by the order we find in the universe, by the regularity, by the existence of laws of nature. That is something I am always in awe of, how the laws of nature we find here on Earth seem to apply all the way out to the edge of the universe. That is quite remarkable. The universe could have been chaotic and very disorganized. But it obeys a set of laws much better than people obey a set of laws here.” 8

Note the language that these eminent scientists use in describing the universe: order, law, harmony, and beauty — the very same words we find in the passages I quoted from early Christian writers.

What those early Christian writers asked is this: whence comes this order? these laws? this harmony? this beauty? Many scientists still give the answer that these writers gave, and that Hermann Weyl, who was himself a Christian believer, gave: “sublime reason.” That is, the divine Reason or “Logos” (which means both “Reason” and “Word”) that St. John’s Gospel tells us about: “In the Beginning was Reason, and Reason was with God, and Reason was God. … Through Him all things were made.”

References

1.. Romans 1:19-20

2.. Catechism of the Catholic Church, section 31.

3.. Catechism of the Catholic Church, section 33.

4.. G.W. Leibniz, “Principle of Nature and Grace Based on Reason.” “[T]he first question we can fairly ask is: Why is there something rather than nothing? After all, nothing is simpler and easier than something. Also, given that things have to exist, we must be able to give a reason why they have to exist as they are and not otherwise.” http://earlymoderntexts.com/assets/pdfs/leibniz1714a.pdf

5.. The quote from St. Irenaeus can be found in section 292 of the Catechism of the Catholic Church. The other eight quotes can be found in The Faith of the Early Fathers, tr. William A. Jurgens (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1970), passages 269, 515, 624, 746, 747, 987, 1050, 2137.

6.. Hermann Weyl, The Open World: Three Lectures on the Metaphysical Implications of Science (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1932), pp. 301-2.

7.. Edward Witten, Video Interview with Wim Kayzer, “Episode 9: Of Beauty and Consolation,” July 21, 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RfwsvSjXkJU.

8.. “Have Aliens Found Us? A Harvard Astronomer on the Mysterious Interstellar Object Oumuamua,” Isaac Chotiner, The New Yorker, January 16, 2019. https://www.newyorker.com/news/q-and-a/have-aliens-found-us-a-harvard-astronomer-on-the-mysterious-interstellar-object-oumuamua