Does Quantum Mechanics Imply That Materialism is False?

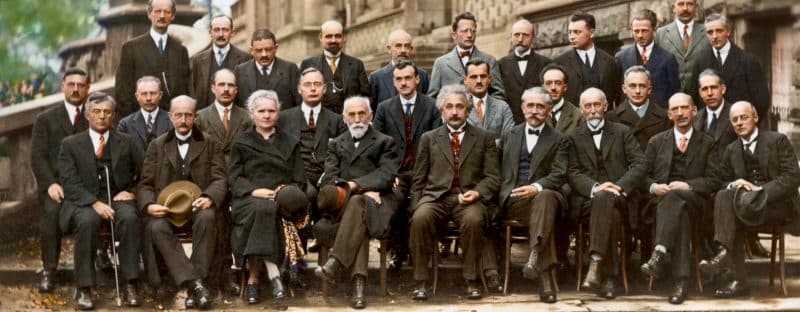

Above: A famous photograph of the 1927 Solvay Conference, at which most of the founders of quantum mechanics were present. [For copyright information go to: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Solvay_conference_1927_%28color%29.jpg]

I. Introduction

2025 is the 100th anniversary of the discovery of quantum mechanics. This discovery was the culmination of a quarter of a century of theoretical and experimental research by many brilliant physicists, including Max Planck, Albert Einstein, and Neils Bohr. In the summer of 1925 Werner Heisenberg made a crucial breakthrough, which he published in September of that year. Over the next few months, Heisenberg and his collaborators Max Born and Pascual Jordan laid down the fundamental principles of quantum mechanics. In the first few months of 1926, Erwin Schrödinger published a series of papers in which he developed an alternative, very-different-looking theory of quantum mechanics and then showed that it is mathematically equivalent to that of Heisenberg, Born, and Jordan. Since that time, quantum mechanics has been successfully applied to explain a vast range of physical phenomena and has passed innumerable precise experimental tests. It is the foundation upon which our understanding of the physical world is built.

Ever since its discovery, it has been generally recognized that quantum mechanics has deep philosophical implications. But despite a century of vigorous discussion and debate among both physicists and philosophers, there is no agreement on what those implications are.

There is consensus that quantum mechanics overthrew the “physical determinism” that had characterized “classical physics”, i.e., the physics that preceded quantum mechanics. Physical determinism is the idea that the laws of physics uniquely determine how events will unfold from any given starting point. It is difficult to reconcile such determinism with the idea that humans have the ability to act freely. The determinism of classical physics therefore had the effect in the 18th and 19th centuries of undermining many people’s belief in free will and thus also in Christianity. Therefore, the discovery of quantum mechanics and the overthrow of physical determinism in the 1920s was a welcome development from a theological perspective. (Though it should be noted that a rather radical way of understanding quantum mechanics, called the Many Worlds Interpretation or MWI, is deterministic. More about MWI below.)

Another philosophical implication of quantum mechanics that has been claimed, but is much more controversial, is that physicalism (also called philosophical materialism) is false. Physicalism is the idea that all of reality is reducible to physics, in other words that there are no non-physical realities. Physicalism has been even more harmful to religious belief than physical determinism.

The claim that quantum mechanics is incompatible with physicalism isn’t just controversial, it seems to be rejected, often with disdain, by the great majority of physicists and philosophers who have written on the subject. And yet it is a conclusion which has been strongly argued for by some of the greatest physicists of the 20th century. In this article I will explain their argument, and why it should be taken seriously.

II. The Argument Against Physicalism Based on Quantum Mechanics

Physicalism is the claim that everything is reducible to physics, including human minds and thoughts. Interestingly, and perhaps paradoxically, physics itself provides strong grounds for doubting this. In the view of some, quantum mechanics implies that there is more to the world, and in particular more to minds, than the equations of physics can describe or account for.

The argument has a long and distinguished pedigree. It goes back at least to John von Neumann’s classic book, The Mathematical Foundations of Quantum Mechanics,1 published in 1932, and to the physicists Fritz London and Edmond Bauer2 in the late 1930s. In the latter part of the twentieth century it was defended by such eminent physicists as the Nobel laureate Eugene P. Wigner3 and Sir Rudolf Peierls.4 Physicists who have written books defending it more recently include Henry Stapp5 of UC Berkeley and Euan Squires6 of the University of Durham in the UK.

Peierls, for example, said,

“[T]he premise that you can describe in terms of physics the whole function of a human being … including its knowledge, and its consciousness, is untenable. There is still something missing.” 7

Wigner stated flatly that physicalism is not “consistent with present quantum mechanics.” 8

One is naturally tempted to ask, especially if one is not a physicalist, how quantum mechanics could have anything to say about minds at all. Isn’t quantum mechanics about things that can be physically measured, such as particles and forces? Of course, it is. But while minds cannot be physically measured, it is ultimately minds that do all measuring. And that, as we shall see, is a fact that cannot be ignored in trying to make sense of quantum mechanics. If one claims that it is possible in principle to give a complete physical description of everything involved when a measurement is made, including the mind of the person who is doing the measuring (traditionally called the “observer”), one is led into difficulties. This is an aspect of what is called “the measurement problem” in quantum mechanics.

In this article, I will explain the argument against physicalism in a way that does not require a prior understanding of quantum mechanics.

II.1. The probabilistic nature of quantum mechanics

The starting point of the anti-physicalist argument is the crucial fact that quantum mechanics is inherently probabilistic. Of course, even in “classical physics” (i.e., the physics that preceded quantum mechanics and that is still adequate for many practical purposes) one often uses probabilities. But that is just due to practical limitations. In classical physics, one could in principle dispense with probabilities if one had complete information about a physical system. That is not true in quantum mechanics. One cannot eliminate probabilities from quantum mechanics. Quantum mechanics is fundamentally about probabilities. Because this is such a key point, it is worth spending some time to see why it is so.

The reason is connected to a fundamental feature of quantum mechanics called “wave-particle duality.” For centuries people debated whether light was made up of particles or waves. The answer turned out to be quite strange. The work of Planck in 1900 and Einstein in 1905 showed that light, in a way that is quite alien to our ordinary experience and intuition, is both wave-like and particle-like. Later, de Broglie and others showed that this wave-particle duality applies across the board — to electrons, for example, and to all other types of matter.

At first glance, wave-particle duality seems not only mysterious but blatantly self-contradictory. A wave is something spread out in space, while a particle is a point. A wave is something whose magnitude can vary continuously, whereas particles are discrete and countable.

To see the apparent contradiction, consider a simple thought experiment. Imagine a flash of light, like a flash bulb going off, from which a light wave ripples out through an ever-widening sphere in space. Let us suppose the light is nearly monochromatic. As the wave travels out, it becomes more attenuated, since its energy is getting spread over a wider and wider area. Now, suppose we set up a light detector at some distance from the flash. Just a box with an aperture and a shutter — essentially, a camera. The farther away the light detector is placed from the flash, the smaller the fraction of the light it will capture. Suppose we adjust the distance of the detector from the flash, or its aperture size, or its shutter speed so that it captures one one-thousandth of the light emitted in the flash — one can do this because these features of the light detector are continuously adjustable. The apparent inconsistency arises if we decide to stop thinking of the light in terms of waves and start thinking in terms of particles.

Suppose the original flash contained, say, fifty particles of light, that is, photons. If there are fifty particles, each carrying approximately the same energy (as the light is approximately monochromatic), and the detector is adjusted to capture 1/1000 of the light, then it would appear that the detector must capture 1/1000 of 50 particles, which is 0.05 particles. But that is impossible, since one can only have a whole number of particles. A wave, being continuous, can be indefinitely attenuated, whereas particles, being countable discrete chunks, cannot.

Quantum mechanics resolves this problem by saying that the detector, rather than capturing 0.05 particles, has a 0.05 probability of collecting one particle. Or, to be more accurate, the “expectation value” or average number of particles it will capture is 0.05 if the same experiment is repeated many times. Wave-particle duality, which gave rise to quantum mechanics in the first place, forces us to accept the conclusion that quantum mechanics is fundamentally about probabilities, a conclusion first clearly drawn by Max Born in 1926.

Roughly speaking, in classical physics, one calculated what actually happens, while in quantum mechanics one calculates the relative probabilities of various things happening. A familiar example is the “half-life” of a radioactive nucleus. Suppose a certain type of nucleus has a half-life of one hour. That means that a nucleus of that type has a 50% chance of disintegrating (or “decaying”) within 1 hour, a 75% chance within two hours, and so on. The quantum mechanical equations do not (and cannot) tell you when a particular nucleus will decay, but only the probability of it doing so within any given period of time. In quantum mechanics, probabilities are encoded in “wave functions.” Wave functions (and the probabilities they encode) evolve in time according to an equation called the Schrödinger equation.

II.2. The crucial issue: probabilities of events

Now we’ve arrived at the crux of the matter. We are talking about probabilities of events — events such as a nucleus decaying or a particle of light entering a light detector. Yet there is something paradoxical about the very notion of “the probability of an event.”

It does not make sense to talk about the probability of an event, unless at some point it stops being a matter of probability and becomes a matter of definite fact. For example, suppose I say that Jane has a 70% chance of passing the French exam. That only means something if at some point Jane will take the French exam and get a definite grade, thus passing or failing. At that point, the probability of her passing no longer remains 70%, but suddenly jumps to 100% if she passes or 0% if she fails. If she will never get a grade and definitely pass or definitely fail, then the probability 70% would lose any meaning. In other words, probabilities of events that lie in between 0% and 100% must at some point jump to 0% or 100% or else they meant nothing in the first place.

This raises a very thorny issue for quantum mechanics. The Schrödinger Equation, which governs how wave functions evolve in time, does not yield probabilities that suddenly jump to 0% or 100%, but rather probabilities that vary smoothly with time and that generally remain in between 0% and 100%. Radioactive nuclei provide a good example.

The Schrödinger equation says that the “survival probability” of a nucleus (that is, the probability of its not having decayed) starts off at 100%, and then falls continuously and monotonically, reaching 50% after one half-life, 25% after two half-lives, and so on — but never reaches zero. No matter how many times one divides by two, one never reaches zero. In other words, the Schrödinger equation only gives probabilities of decaying, never an actual decay! If there were an actual decay, the survival probability should jump to 0 at that point.

To recapitulate the key points:

- First, the equations in quantum mechanics yield probabilities.

- Second, to mean anything, those probabilities must be the probabilities of definite events that happen or do not happen.

- Third, when definite events happen, some probabilities should jump to 0% or 100%.

- However, and fourth, the equations of quantum mechanics do not describe such jumps.

One begins to see how one might reach the conclusion that not everything that happens is describable by the equations of physics.

II.3. Why minds might matter: observations and observers

So how do minds enter the discussion? The traditional understanding (the so-called Copenhagen interpretation) is that the definite events that happen or do not happen, and whose probability one calculates in quantum mechanics, are the outcomes of measurements or observations (the words are used interchangeably in this context). If someone (traditionally called “the observer”) checks to see whether, say, a nucleus has or has not decayed (perhaps using a Geiger counter), he or she must and will get a definite answer. When the observer comes to know that answer, his or her knowledge suddenly changes. At that point, the observer has to set the survival probability of the nucleus either to 0% or to 100% depending on what he or she has learned from the measurement. This sudden change in probabilities must, of course, be reflected in the wave function that encodes those probabilities. The wave function must suddenly change. This traditionally is called the “collapse of the wave function.”

Schematically, the wave function of a radioactive nucleus looks as follows, as long as no measurement is made:

ψ(nucleus) = α(t) ψ(decayed) + β(t) ψ(not decayed)

Obviously, there is more that can be said about a nucleus besides whether it has decayed or not. Thus, the wavefunction can have more information in it than I am showing. The time-dependent coefficients α and β are called “probability amplitudes.” When no measurement is made, these coefficients evolve in time according to the Schrödinger equation. If one makes a measurement at time T to see whether the nucleus has decayed or is still there, the probability that one will find that it has decayed is given by |α(T)|2 (that is, the square of the “absolute value” of α(T)) and the probability that one will find that it has not decayed is |β(T)|2. This prescription for extracting probabilities from wave functions by taking the absolute squares of amplitudes is called the “probability rule” or the “Born rule,” after Max Born who proposed it in 1926. An important point to note is that neither wave functions nor the “amplitudes” in them are themselves probabilities. (They could not be, since their values are in general complex numbers, that is, numbers containing the square-root of minus 1, whereas probabilities are real numbers.) Rather, wavefunctions are related to probabilities by the Born rule, which comes into play when measurements are made. That is why I said that wave functions “encode” probabilities, rather than saying that they simply are probabilities.

What does the wave function of the radioactive nucleus look like right after the measurement? Well, it depends what the outcome of the measurement was. If the measurement showed that the nucleus decayed, then right after the measurement the wave function looks like this:

ψ(nucleus) = ψ(decayed) .

If, on the other hand, the measurement showed that the nucleus did not decay, then right after the measurement the wave function looks like this:

ψ(nucleus) = ψ(not decayed)

In other words, one “throws away” or “cuts off” the part (or parts) of the wave function that describe outcomes that are known not to have happened and retains only the part corresponding to the outcome that is known to have happened, resetting its coefficient (or amplitude) to be 1 (or a complex number of magnitude 1), because now its probability is known to be 100%.

One sees that wave functions have two ways of changing. When no measurement is made on a system, the wave function evolves according to the Schrödinger equation, which is a continuous, predictable, “unitary” evolution. (“Unitary” is a mathematical term.) No information is lost during this unitary evolution; so that from the wave function at a later time one could in principle reconstruct what it was at earlier times by running the Schrödinger equation backwards. When a measurement is made, however, the wave function changes in a quite different manner: in the traditional parlance, it “collapses.” This is a sudden, unpredictable (except probabilistically), and non-unitary change. Knowing the wave function after a measurement does not allow one to reconstruct what the wave function was before, just as knowing the wave function before a measurement does not allow one to predict, except probabilistically, what it will be afterwards.

Many physicists find the idea of “the collapse of the wave function” strange. It goes against the intuition that physical processes should unfold in a gradual and continuous way, as described by the equations of classical physics and also by the Schrödinger equation. As I have mentioned, however, the discontinuous “collapse” of the wave function that occurs as the result of a measurement simply reflects the sudden change of the observer’s knowledge.

Probabilities of events refer to someone’s state of knowledge. For example, before I knew the outcome of Jane’s exam I could only say that she had a 70% chance of passing; whereas after I know I must say either 0 or 100%. Since wave functions encode probabilities, they encode someone’s state of knowledge. When that observer’s knowledge changes (as it does suddenly at the end of a measurement), the wave function must change suddenly to reflect this.

To quote Sir Rudolf Peierls again:

“[T]he moment at which you can throw away one possibility and keep only the other is when you finally become conscious of the fact that the measurement has given one result. … You see, the quantum mechanical description is in terms of knowledge, and knowledge requires somebody who knows.” 9 [emphasis added]

Heisenberg himself wrote,

“The discontinuous change in the probability function, however, takes place with the act of registration [of the result of the measurement], because it is the discontinuous change of our knowledge in the instant of registration that has its image in the discontinuous change of the probability function.” 10

The intuition that physical processes unfold in a continuous manner is not necessarily wrong. But the collapse of the wave function is reflecting a change in knowledge, and that is not necessarily just a physical change. Indeed, the point of the anti-physicalist argument I have been sketching is precisely that it is not.

An obvious question is why one would need to talk about knowledge and minds at all. Could not a physical device that totally lacked consciousness (say, a Geiger counter) be the “observer” and carry out a “measurement”? According to von Neumann, Peierls, and others, the answer is no. That is why Peierls, who was asked exactly this question, answered that the collapse of the wave function required the observation of “somebody who knows,” not “something.” The reason is the following.

Suppose the “observer” were just a purely physical entity, such as a Geiger counter. Then one could, in principle, write down a bigger, more inclusive wave function that described not only the thing being observed, say a radioactive nucleus, but also that purely physical observer, say the Geiger counter. That bigger, more inclusive wave function would evolve in accordance with the Schrödinger equation. And because of that, the probability amplitudes would not collapse to give probabilities of 0% or 100%, i.e., a definite outcome, but rather probabilities that remain somewhere in between. In other words, the bigger wave function will have an amplitude for the nucleus having decayed and the Geiger counter having registered its decay, and an amplitude for the nucleus not having decayed and the Geiger counter having registered its non-decay. No collapse occurs to just one of these possibilities.

That is the point that I made earlier: as long as only purely physical entities are involved, they are described by wave functions that are governed by an equation (the Schrödinger equation) that says that the probabilities do not collapse to a definite result. One remains trapped in a limbo of probabilities rather than the world of definitely observed facts.

But here, many people would object that observers, such as human beings, are physical. We have bodies made of atoms. The sensory organs and brains with which we carry out measurements and observations are made of atoms. Therefore, they must be describable by physics. That is all obviously true. Moreover, just as one could include a Geiger counter in a bigger, more inclusive wave function, one should, in principle, be able to include also the observer’s sensory organs and brain in an even bigger and even more inclusive wave function. Experimental devices, such as Geiger counters, are just extensions of our sensory organs. Or, equivalently, our sensory organs could be considered part of the experimental apparatus just like the Geiger counter.

This leads us to a basic question. In quantum mechanics, there is always a “system” that is measured and that is described by a wave function, and an “observer” who makes observations or measurements of the system that collapse the wave function. The question is where the “system” ends and the “observer” begins.

Suppose that I am the observer, and the system I am studying is a radioactively unstable nucleus. One could count only the nucleus as the system, and consider the Geiger counter, my sensory organs, the part of my brain that processes the information from my sensory organs, and me in toto as the observer. Alternatively, one could lump the Geiger counter in as part of the system, meaning that there would be a wave function describing both the nucleus and the Geiger counter. Everything else would be considered the observer. Or one could consider not only the nucleus and the Geiger counter but also my sensory organs as part of the system. One could move more and more over from the observer side of the line to the system side. So it is somewhat arbitrary where the line between the “system” and the “observer” (sometimes called the “Heisenberg cut”) is drawn. Nevertheless, the logic of quantum mechanics requires that it must be drawn, and it must be drawn in such a way that there is something on each side of it. If one tries to put everything on the “system” side, so that there is nothing left on the “observer” side — so that there is no longer an observer at all, or any observation — you end up with a wave function that never collapses and probabilities that never jump to give definite outcomes. To quote Eugene Wigner again:

“[E]ven though the dividing line between the observer, whose consciousness is being affected, and the observed physical object can be shifted towards the one or the other to a considerable degree, it cannot be eliminated.” 11

What is it that must remain on the “observer” side of the “Heisenberg cut”? It cannot be any part of his or her body, for these are physical and should be describable by wave functions. It is hard to escape the conclusion that there is some aspect of the mind of the observer that is non-physical. And that is the conclusion that Wigner, Peierls, and some others have drawn.

II.4. Objections to the traditional understanding

The way of understanding quantum mechanics that I have just described was once generally understood and accepted. It is variously called the Traditional Interpretation, the Standard Interpretation, and the Orthodox Interpretation. Some use the term “Copenhagen Interpretation.”

Many objections are made to the traditional understanding. One is that it talks about the observer whose measurement collapses the wave function of the system. But there are many human beings in the world and several of them might be observing the same system. Which one is “the” observer? This question is sharpened in a paradox invented by Eugene Wigner,12 which has come to be called the “Wigner’s Friend Paradox.” Wigner imagined doing an experiment employing a friend as a lab assistant. Suppose the experiment uses a Geiger counter to detect the decay of a radioactive nucleus. Late in the evening, Wigner goes home to bed leaving his friend in charge overnight. At 3 o’clock in the morning, Wigner’s friend checks the experimental apparatus and finds that the nucleus has decayed. If we regard Wigner’s friend as the observer, then the wave function collapses at 3 o’clock. At 9 o’clock in the morning, Wigner shows up at the lab and learns from his friend that the nucleus has decayed. Suppose that we now regard Wigner as the observer and his friend as merely a part of the experimental apparatus used by Wigner. In that case, the wave function collapses when Wigner knows the outcome, that is, at 9 o’clock. So, which is it? There is a simple resolution. A wave function encodes a particular observer’s knowledge of a particular system. When Wigner’s knowledge changes, it collapses the wave function that encodes Wigner’s state of knowledge. When Wigner’s friend’s knowledge changes, it collapses the wave function that encodes Wigner’s friend’s state of knowledge. If we want to make it less personal, one can say that a wave function encodes the knowledge of a class of observers who have the same information about the system.

Another question often asked is who qualifies as an observer? A human being certainly does, but what about a chimpanzee? Or a cat? Or a fish? Or a worm? Or a bacterium? Or an atom? Or a subatomic particle? One possible answer is very simple: Anything that is capable of knowing the outcomes of measurements is an observer.

A famous objection to the traditional understanding of quantum mechanics was made by Erwin Schrödinger himself in the form of a thought experiment now called the Schrödinger’s Cat Paradox. One puts a cat into a box with an apparatus that will kill the cat if a certain radioactive nucleus decays, but not otherwise. (For example, a detector such a Geiger counter could be attached to a device that breaks a vial of poison gas. Of course, this is just a thought experiment; no one actually does this.) The wave function of the system composed of radioactive nucleus plus killing apparatus plus cat will have amplitudes for both the cat being alive and the cat being dead. Until, that is, the observer opens the box and checks to see if the cat is alive, when he or she must get a definite result, collapsing the wave function.

Does that mean that quantum mechanics says that the cat is neither alive nor dead until someone looks? That is the impression that many people have, but it is not what the traditional understanding of quantum mechanics really says. If I open the box, I can see whether the cat is alive or dead at that moment, but (if it’s dead) I can also do all sorts of tests of forensic pathology, such as measuring cat’s body temperature, lividity, and so on, to determine how long the cat has been dead. Other observers may do their observations of the same cat at different times than I, but we will all agree on the time of death of the cat as long as we do our measurements and forensic pathology correctly. So quantum mechanics as traditionally understood may be strange, but it does not really say absurd things about cats being alive and dead at the same time. Before I make my observation, the wave function contains probability amplitudes corresponding to a vast array of possible situations, not just “cat alive” and “cat dead.” These include the cat still being alive, the cat having died five minutes ago and still being warm, the cat having died two hours ago and being cold, and so forth. When I make my observation, the wave function collapses to just one of those possibilities.

Many people wonder why we do not just say that the wave function collapses at the point when the cat actually dies. But this is not correct. As long as no measurement is made, all one has is a wave function that is evolving in accordance with the Schrödinger equation. That evolution is perfectly continuous and unitary and preserves as parts of the wave function all the amplitudes corresponding to the different possible things that can happen to the cat, including its dying at different times. The Schrödinger equation does not select out one of these possibilities as the one that really happens. It is the selecting out of one possibility as corresponding to reality and the “throwing away” (to use Peierls’s words) of the others as not corresponding to reality that is the “collapse” of the wave function.

It is true, however, that something dramatic and important happens to the wave function of the system when the decay of the nucleus causes a change in the condition of macroscopic objects such as a Geiger counter or cat. That something is not “the collapse of the wave function” but rather rapid “decoherence.” Some physicists have the impression that decoherence is the same thing as wave function collapse, and therefore that all one needs for a measurement to take place is a macroscopic object such as a Geiger counter, and one can dispense with any consideration of conscious observers and minds. But they are wrong. Decoherence is not the same thing as wave function collapse. (Decoherence in the Schrödinger’s Cat experiment would mean that the “amplitudes” for a live cat and a dead cat can no longer in practice be shown to coexist in the wave function through an “interference experiment.” But it does not mean that one of those possibilities is selected out as the only real state of affairs, which is what traditionally is assumed to happen as the result of a measurement.) This gets into questions beyond the scope of this article, however.

II.5. Ways out for the physicalist

If one is a physicalist, what options remain? There are basically two. The first is simply to say that wave functions never collapse. There is nothing special about “observers,” no “Heisenberg cut,” no fundamental distinction between “system” and “observer.” There are only purely physical systems, which are adequately and exhaustively described by wave functions that evolve in accordance with the Schrödinger equation. That leads to what is called the Many Worlds Interpretation (MWI). Because wave functions never collapse, all possibilities remain always in play. And because we know that some possibilities truly do happen (we see them happen), one seems forced to say that all possibilities truly do happen, but they happen in distinct branches of the wave function.

There are branches where Schrödinger’s cat is alive, other equally real branches where it is dead. There are branches where you are reading this article, other branches where “you” are lying on a beach somewhere, other branches where “you” were never born, and so on. All equally real. Because of decoherence, these branches do not “interfere” with each other (or, to be more accurate, their interference is utterly negligible and indiscernible), so for all practicable purposes they have split off from each other as different “worlds.”

Most physicists find the idea that every person exists in an infinite number of equally real versions in different “worlds” too implausible to accept. But plausibility aside, it is far from clear that the Many Worlds Interpretation of quantum mechanics is even a tenable idea. One difficulty it has is in explaining how wave functions are connected to probabilities. One has abandoned any fundamental observer-system distinction, and therefore any fundamental distinction between “measurements” and other processes. That being the case, there is no distinct point at which to apply the “Born rule.” In the traditional understanding of quantum mechanics, the Born rule for computing probabilities comes into play when measurements are made and wave functions collapse. The Born rule tells one the probability that it will collapse in this way or that way. In the Many Worlds Interpretation, however, there are no collapses of wave functions, only the evolution of wave functions by the Schrödinger equation. And it is generally agreed that one cannot derive the Born rule for probabilities — or indeed any statement at all about probabilities — from the Schrödinger equation alone.

This, of course, would be a disaster for quantum mechanics. If quantum mechanics cannot predict probabilities, it cannot predict anything. It would cease, then, to have any contact with empirical facts.

The second option for the physicalist is to change the rules of the game: to replace quantum mechanics by some fundamentally different theory. The two most popular ideas of this type are called Bohmian mechanics13 and the GRW14 theory. I will not explain or critique these. I will only say that these alternative theories sacrifice much of the beauty and simplicity of quantum mechanics, while at the same time it very doubtful that they can reproduce all the wonderful successes of quantum mechanics.

III. Conclusion

The argument I have explained above leads to the following conclusion. If one is a physicalist, and assumes that the basic structure of quantum mechanics as it has been for the last 100 years is correct — as all evidence to date indicates — one seems forced into the Many Worlds Interpretation with all of its implausibility and problems of consistency. For the physicalist, this is a very tight corner to be in.

Most working physicists are probably not familiar with this argument against physicalism, despite its distinguished pedigree (von Neumann, Peierls, Wigner, and others). Most of those who do know about it tend to dismiss it out of hand. This is probably mostly due to a deeply ingrained physicalism that cannot take at all seriously the idea that consciousness is anything other than a purely physical phenomenon fully explicable by physics. Some of them are therefore willing to accept the Many Worlds Interpretation as the lesser of two philosophical evils. Others pin their hopes on the idea that quantum mechanics is actually wrong and will be replaced eventually by some better theory.

But it is not only some physicalists who have trouble accepting quantum mechanics and hope that it will be replaced by something else. Some religious people have also expressed great discomfort with quantum mechanics as traditionally understood, including Catholics, such the historian Stanley Jaki, the physicist Peter E. Hodgson, and the philosopher Mortimer Adler. What disturbs them about quantum mechanics is not that it seems to point to the importance of mind or consciousness, but rather that it seems to give too great a role to them. Indeed, they see quantum mechanics as undermining the idea that there is an objective reality that is what it is no matter what any finite mind knows about it or observes about it.

The problem that they have with quantum mechanics comes from the fact that the fundamental quantities calculated in quantum mechanics are not straightforward descriptions of the way the physical world is in itself, as was the case in classical physics. As we have seen, wave functions encode probabilities, and therefore seem to refer only to the state of knowledge about the physical world of particular observers or classes of observers. This does not lead to subjectivism in the sense of a multiplicity of irreconcilable viewpoints, as some fear. Different observers can have different states of knowledge (which change as they make measurements), but these different states of knowledge will all be consistent with each other as long as the observers do not make mistakes in their measurements. Nevertheless, it is hard to see how one could stitch together all these different observers’ states of knowledge into a single unified and complete picture of “objective reality.” At best, one seems to be left with a patchwork quilt or collage of partial pictures of reality that even together do not give an exhaustive description of the world as it is “in itself.” Indeed, the “collapse” of the wave function, whereby one wave function is replaced by another that differs from it in a discontinuous way, is itself a kind of seam in the patchwork quilt.

Some people respond to this problem by adopting a purely instrumentalist view of physics. According to this view, physics is nothing except a set of mathematical rules that relate our measurements of the world to each other, but one that does not presume to say anything about reality that goes beyond or lies behind what we measure. This could even be taken in an idealist direction, in which one says that reality consists of nothing but the set of our experiences, and that the laws of physics simply give correlations among those experiences.

In a long Appendix, I discuss these questions, and in particular I show that there is at least one way (there may be others) to understand quantum mechanics that not only avoids physicalism (with all its problems) but also avoids the kinds of things that people like Jaki, Hodgson, and Adler worried about and preserves the common-sense idea that there is a single objective reality and that physics tells us about this reality (although not everything about it).

So while quantum mechanics is very strange, counterintuitive, and in some ways unsettling, it poses no threat to the core metaphysical principles held by Catholics. On the other hand it very much poses a threat to physicalism. So, on this hundredth anniversary of its discovery, we have every reason — not only scientific, but also philosophical — to celebrate this great triumph of the human intellect.

References

1. John von Neumann, The Mathematical Foundations of Quantum Mechanics, English translation (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1955).

2. Fritz London and Edmond Bauer, La Théorie de l’Observation en Mécanique Quantique (Paris: Herrmann and Cie, 1939).

3. Eugene P. Wigner, “Remarks on the Mind-Body Question,” in A Scientists Speculates, ed. I.J. Good (London: William Heinemann Ltd., 1961), reprinted in Eugene P. Wigner, Symmetries and Reflections: Scientific Essays (Woodbridge, Conn., Oxbow Press, 1979).

4. Rudolf Peierls, “Observation in Quantum Mechanics and the ‘Collapse of the Wave Function,’” in Symposium on the Foundations of Modern Physics, eds. Pekka Lahti and Peter Mittelstaedt (Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Co., 1985).

5. H.P. Stapp, Mind, Matter, and Quantum Mechanics (New York: Springer-Verlag, 1993).

6. Euan Squires, Conscious Mind in the Physical World (London: Adam Hilger, IOP Publishing Ltd., 1990).

7. R. Peierls, quoted in P.C.W. Davies and Julian R. Brown, The Ghost in the Atom: A Discussion of the Mysteries of Quantum Physics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986), p. 75.

8. Eugene P. Wigner, Symmetries and Reflections, p. 176.

9. R. Peierls, in P.C.W. Davies and Julian R. Brown, The Ghost in the Atom, p. 74.

10. Werner Heisenberg, Physics and Philosophy. (New York: Harper & Row., 1958), p. 28.

11.. Eugene P. Wigner, Symmetries and Reflections, p. 172.

12. Eugene P. Wigner, Symmetries and Reflections, p. 176.

13.. David Bohm, “A Suggested Interpretation of the Quantum Theory in Terms of ‘Hidden Variables’ I,” Physical Review 85, 185 (1952).

14. G.C. Ghirardi, A. Rimini, and T. Weber, “Unified dynamics for microscopic and macroscopic systems,” Physical Review D34, 470 (1986).

15. R. Peierls, in P.C.W. Davies and Julian R. Brown, The Ghost in the Atom, p. 74.

16. D.Z Albert and B. Loewer, “Interpreting the Many Worlds Interpretation,” Synthese 77 (2), 169 (1988).

17. Kirk, Robert, “Zombies”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2015 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2015/entries/zombies/>.

Appendix: Saving objective reality within the framework of quantum mechanics

The anti-physicalist argument is based on the traditional (or “Copenhagen”) understanding of quantum mechanics, and that seems to have its own problems. Perhaps the most serious of these is how to make sense of the notion that there is a single objective reality or “state of affairs” that is independent of what any human being or other finite observer knows about it. It is not an easy question to answer. In the same interview from which our earlier quotes of him are taken, Peierls was asked, “So you think consciousness plays a crucial role in the nature of reality?” Peierls responded, “I do not know what reality is.” 15 One can see why many people have regarded the traditional interpretation of quantum mechanics as philosophically dangerous.

What I will explain now is a speculative hypothesis that allows an understanding of quantum mechanics that is consistent with there being at all times a single, objective “state of the world” and that is also consistent with there being a single, comprehensive and complete description of the world (though not, of course, a description that could be known by any finite mind). It is quite similar to what has been called the “Single Mind” Interpretation.16 I will call it the “traveling minds hypothesis.” I do not claim that it is the only one that allows a “realist” understanding of quantum mechanics or is the best such hypothesis. I do think that it shows that at least one “realist” hypothesis exists that is consistent with the traditional postulates of quantum mechanics and with everything else we know about the world.

The traveling minds hypothesis supposes that mind or consciousness is a constituent feature of the universe just as real as matter and as fundamental as matter in the sense of not being reducible to matter. The traveling minds hypothesis has features in common with both the traditional Copenhagen Interpretation and the Many Worlds Interpretation, though it appears to avoid the problematic features of each. Like the Many Worlds Interpretation, it posits a wave function of the entire physical universe that never collapses. When a measurement is made, the amplitudes corresponding to the different possible outcomes of the measurement very rapidly decohere from each other (because observers, who are conscious beings, necessarily have bodies that are macroscopic in scale). This means that any “interference” effects among these amplitudes are utterly negligible, and that for all practical purposes it is as though these outcomes happened in separate branches of reality, or separate “worlds.” The crucial assumption of the traveling mind hypothesis is that when such a decoherence or splitting into branches takes place all mind and consciousness everywhere in the universe travels down just one of the branches. All the alternative branches remain devoid of mind and consciousness.

In this picture, the “selection” of one possible outcome of a measurement as the one that is actually observed to occur is not associated with a sudden change in the wave function itself (i.e., its “collapse”), but rather with something that happens to mind and consciousness, namely its taking just one of the many decohered branches. One does not have to “throw away” the parts of the wave function corresponding to the outcomes that were observed not to occur. It is simply that those parts of the wave function of the universe describe branches that have no consciousness associated with them. Those outcomes are not observed to occur simply because there is no mind or consciousness that observes them.

This picture (unlike the Many Worlds Interpretation) allows the Born rule to be applied. The Born rule gives the probability for mind (i.e., all mind in the universe) will travel down a particular branch. It is not a rule that governs matter (like the Schrödinger equation), but a rule that governs mind. The Born rule does not have to be derived from the Schrödinger equation; it is a distinct law of nature.

The traveling minds hypothesis avoids the two major defects of the Many Worlds Interpretation: First, it has a place for the Born rule. Second, it does not posit the existence of an infinite number of versions of every person, one in each branch. At a branching, the mind of a person — and thus the “person” himself or herself — travels down only one branch, the same branch that all other minds also travel down. The other branches of the wave function describe entities that have physical structures that are the same (or nearly the same) as that of the body of the person, but these structures have no mind associated with them. (In the colorful jargon of contemporary philosophy of mind, these entities are “philosophical zombies.” 17)

“Philosophical zombies” are usually discussed by philosophers as logical possibilities that are not natural possibilities. (That is, it is not illogical to posit such entities, but it is supposed that they cannot exist in the real world.) In the traveling minds picture, such philosophical zombies are indeed not natural possibilities in that single “world” or branch that is traveled by all mind and consciousness, which is obviously the world that all conscious beings in the universe inhabit. Every person can therefore be assured that every other person in his or her world also has a mind and is not a philosophical zombie. The idea that the other, “unconscious branches” of the world (so to speak) have philosophical zombies may be disconcerting, but obviously does not disagree with anything in our experience, nor could it. In any case, those branches, being devoid of anything that could experience them, have only a shadowy existence. There is nothing to stop one from regarding them (in the spirit of the philosopher Bishop Berkeley) as not existing at all, or (in the spirit of Aristotle) as “potential” worlds that were never “actualized.”

It may seem a high price to pay to posit such entities as philosophical zombies in the “other” branches of the world, but Ockham’s Razor would seem to justify it. The laws of physics (the Schrödinger evolution of the wave function of the universe) presents us with a vast number of other branches of the wave function. But it is gratuitous to posit minds connected to all those other branches. Without a theoretical or empirical reason for doing so, it is more economical not to do so. Despite this, physicists have generally assumed that if other branches of the wave function exist (that is, were not “thrown away” in wave function collapse) they have beings with minds in them just as our branch has. Not only is this assumption made, but few physicists even notice that it is an assumption. Why is this assumption made so automatically and unquestioningly? The reason may be that it is the most “symmetric” assumption to make. Why should only one branch of the wave function have in it mind and consciousness and not the others? But this breaking of symmetry is no worse than what is assumed to happen in wave function collapse in the traditional understanding of quantum mechanics, where there are many possible outcomes of a measurement, but only one of them occurs.

Another reason for the automatic assumption that consciousness exists in other branches, is the prior assumption of physicalism. If mind is ultimately reducible to physics, then whenever certain physical structures exist mind should also exist. We have already seen, however, that physicalism in the context of quantum mechanics leads to trouble: First and foremost, it seems to compel the Many Worlds Interpretation, which has no room for the Born rule. Once we abandon the problematic assumption of physicalism, there is no a priori reason to suppose that mind or consciousness exists in any branch of the world besides the one we all experience. And once we allow consciousness to be a constituent feature of the world as real as matter and irreducible to it, it can be the “pointer” or “index” that makes the “selection” among possible outcomes of measurements, thus making sense of the Born rule.

The traveling minds hypothesis says that there are two aspects of the world, mind and matter, that are equally real and equally fundamental. Each has a law associated with it. The law obeyed by matter (the Schrödinger equation) is deterministic. The law obeyed by mind (the Born rule) is not deterministic. This view of the world corresponds to common sense and to our intuitions about ourselves. Moreover, the traveling minds hypothesis posits a single, objective and unambiguous state of affairs at all times. There is a unique, adequate, and exhaustive description of it, which consists of, first, the “wave function of the universe” and, second, the path traveled by mind in that constantly branching set of possibilities.

Is this picture self-consistent? One might worry about the fact that decoherence is not an instantaneous event. It takes a finite time for branches that are splitting apart to definitively part company so that interference between them becomes negligible. During that brief period, would minds be inhabiting two or more branches at once, because the branches had not yet fully separated? Might minds not briefly experience cats being simultaneously alive and dead during the interval when those two amplitudes have not decohered? This seems not to be a problem, however. The reason is that it also takes a finite time for the neural processes to occur that are associated with having a conscious experience. That time is much longer than the typical decoherence time when macroscopic objects, such as cats, are involved. Consequently, we never experience multiple branches at once. (It should be noted that this is not just an issue for the traveling minds hypothesis, but also for the Many Worlds Interpretation. The rapidity of decoherence is the resolution in both cases.)

Some may dislike the traveling minds hypothesis on the grounds that it has a “dualistic” flavor. But it is only dualistic in the sense that it recognizes matter and mind as equally real and equally fundamental aspects of the world. Mind is seen as something “over and above” matter but not “apart” from matter. The hypothesis not only posits both matter and mind as constituent features of the world, but also has something definite to say about how they relate to each other. It is a logically coherent framework in which mind and matter each have a place.

Summary

The “measurement problem” in quantum mechanics has bedeviled both physicists and philosophers of physics for a century. The core of it is the question of how the probabilities encoded in wave functions get resolved into definite outcomes. If one assumes physicalism, it seems impossible to answer this question satisfactorily. For if everything is physical, there should be a wave function that includes everything: the whole universe and all of its contents. That single universal wave function cannot collapse to definite outcomes, but must evolve in accordance with the Schrödinger equation, which leaves all possibilities in play. One is then trapped in a limbo of “probability amplitudes” rather than a world of definite facts. This limbo of “probability amplitudes” is called the Many Worlds Interpretation (MWI) of quantum mechanics. It is not only exceedingly implausible in the eyes of most physicists, but probably untenable. It does not even have a way to convert the probability amplitudes in the wave function into actual probabilities let alone into definite outcomes. That is because in the MWI everything that happens does so in accordance with the Schrödinger equation, and that equation by itself cannot yield the all-important “Born rule” that relates the probability amplitudes to probabilities of events.

The traditional understanding of quantum mechanics avoids this disaster by invoking special events called “observations” or “measurements,” which result in definite outcomes, namely the known results of the observations or measurements. A special rule (the Born rule) is invoked when measurements happen to relate the wave function that has been calculated to the result of the measurement. The Born rule specifies how the probabilities of outcomes are computed from the mere “probability amplitudes” in the wave function. It is a separate rule, not obtainable from the Schrödinger equation, that comes into play only when the special kinds of events called observations or measurements take place.

The logic of the traditional understanding of quantum mechanics leads one to posit “observers,” who perform the special events called measurements and who consummate those measurements by knowing their results. It is these observers who are not allowed to be subjected entirely to physicalist reductionism. Nevertheless, accounts of the traditional understanding of quantum mechanics (given in textbooks, for instance) typically avoid discussing “the observer” explicitly. There is talk about “observables,” measurements of those observables, and outcomes of those measurements, but the observer remains off stage or in the background. This reticence is understandable. It reveals a discomfort with the notion that observers have some privileged status, which is hard if not impossible to justify on physicalist grounds. The observer is the proverbial “elephant in the room.”

But this unwillingness to face up to the question of what the observer is has the unfortunate consequence of making measurements seem like ordinary, purely physical events. It also causes attention to be focused on the wave function rather than the observer. Consequently, the “definite outcome” is described as something that happens to the wave function itself (a “collapse”) rather than as something happening to the observer. But the attempt to keep the observer out of the picture only forces him (or her) to reappear in an oblique way. One has to interpret these wave functions, which are frequently “collapsing” as the result of observations, as representing no longer the world in itself, but the observer’s knowledge of the world. (That is the only way to make sense of the “collapse.”) But this too is not fully satisfactory, as it precludes a fully realist understanding of quantum mechanics. One is left with just a patchwork of wave functions representing various observers’ states of knowledge, rather than the possibility of a single, synoptic picture of reality.

The remedy is to face the question of the observers’ status and nature squarely. It is to accept the anti-physicalist implications of quantum mechanics fully, and to recognize that the minds of observers are irreducible to physics. Once one takes that step (which has been taken by many), the natural next step is to see that what happens at a measurement is best thought of not as a collapse of the wave function, but as a “collapse” of consciousness into one branch of the wave function. The “roads not taken” are still there, but simply not taken by mind or consciousness, and therefore not experienced by any observer. For all practical purposes, they might as well not be there, and in practice it makes sense to “throw them away.” But that is a matter of practical bookkeeping. From a philosophical standpoint, the “traveling mind hypothesis” makes more sense. All mind in the universe travels down a single path through the ever-ramifying wave function of the universe. This allows a simple realist view of quantum mechanics. In sum, there is a strong argument that quantum mechanics is incompatible with physicalism, while being perfectly compatible with the notion of a single objective reality and a realist understanding of physics.