Childhood Cancer and the Problem of Evil

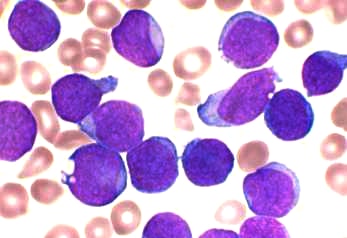

Above: Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Smear [For copyright information, see https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Acute_lymphoblastic_leukaemia_smear.jpg]

What is evil?

Webster’s Dictionary defines evil as “(1) anything that causes displeasure, injury, pain, suffering, etc.,” or “(2) moral depravity, wickedness, anything morally bad or wrong.” 1 All of us have experienced evils; they are part of the human condition. Suffering is defined as “the bearing or undergoing of pain, distress or injury.” It is our response to our experience of an evil, and it can be emotional, intellectual or spiritual. We seek relief from or at least understanding of our suffering, and, for many, philosophy or religion is key to obtaining this. For example, Buddhism is a religious system centered on the understanding of and ultimate deliverance from suffering. And, for Christians, the mystery of the suffering and death of Christ lies at the heart of their faith.

As we suffer or watch others suffer, we ask why this suffering occurs. We want explanations. Sometimes they are evident, but often they are not. When suffering is acute many seek explanations from God. “Why have You done this to me?” or “Why have You allowed this to occur?” This is the existential basis for the philosophical “problem of evil.” It is an effort to reconcile the existence of evil and suffering with the all-powerful, all-caring and all-knowing God worshiped by Jews and Christians.

There are many formulations of the problem of evil; here is one.2

Proposition 1: If an all-powerful, all-caring and all-knowing God exists, then evil should not exist.

Proposition 2: There is evil in the world.

Conclusion: Therefore, an all-powerful, all-caring and all-knowing God does not exist.

One solution to this problem is to acknowledge the presence of evil in the world and come to the conclusion that God is not all-powerful. For example, Zoroastrianism and Manichaeism were religions that saw the cosmos as a struggle between a powerful god of good and a powerful god of evil each of whom caused things in the world. St. Augustine as a young man was a Manichaean for many years. He later became a Christian and actively opposed Manichaeism.

Another response to this formulation of the problem of evil is to critically assess the nature of evil and its origins. Proposition 2 posits that there is evil in the world. Where does it come from? Some evils are created by the free will actions of human beings. Examples include the murder and mayhem found in history books and in the daily news. God is not the cause of these evils. Some may object that while God has not caused them, nonetheless God has not acted to prevent them. The common answer to this objection is that God has chosen to create human beings with free will. If God were actively to prevent all human actions that lead to evils, human beings would not be truly free. Most people accept this answer as showing that the presence of human-caused evils in the world is compatible with faith in an all-powerful, all-caring and all-knowing God.

A more difficult problem is the presence of evils that are not caused by human choice and action. Examples include powerful storms and earthquakes that destroy cities and towns, droughts that lead to crop failures and famine, and birth defects that leave human beings without the use of one of their faculties. Has God created these evil things and willed humans to endure their attendant miseries?

St. Augustine, in his maturity, grappled with this question.3,4 He rejected the assertion that God made evil things. Rather, he concluded that every thing that God creates is good, but that there are gradations of goodness. What we humans consider evil is a lack of complete goodness, or a corruption of prior more complete goodness. One can take the phenomenon of blindness as an example. Consider a man born blind. Did God create an evil thing called “blindness”? No, he created a good thing called a man. That man, whether blind or seeing, is a wonderful creature made in the image and likeness of God, and for his existence we ought to give God praise. A blind man is as much a child of God as another man born with sight. Blindness is not a thing that God brought into existence, rather it is the absence of something good, namely the power of sight. The power of sight is something that exists and is good. That there is such a thing as the power of sight is astonishing and something that we ought to thank God for. But the blind man lacks this good. It is a good that “belongs” to human nature, and so its absence causes suffering.

St. Thomas Aquinas came to similar conclusions about the problem of evil.5 He also thought that evil is not a thing, but is rather a “privation,” a lack of being in something good rather than something that exists in itself. Aquinas also distinguished between natural evils and moral evils. Natural evils are not the result of human choice and action— for example, human beings do not cause volcanic eruptions, whereas moral evils result from human will.

These insights of Augustine and Aquinas are logical and cogent and take us some way toward an answer to the “problem of evil.” They provide a reasonable argument that God does not “create” evil per se, because to “create” in the theological sense is to give being, while evil is a privation of being. (A helpful analogy might be that a lamp, in a sense, creates light. But we would not say that it “creates darkness” just because there are places it does not illuminate.) Neither St. Augustine nor St. Thomas meant to imply that evils are not real or not evils. Because the power of sight in a sense “belongs” to human nature (whereas it does not belong to the natures of plants or of some animals), it is for a human being indeed a “privation” and a “physical evil” not to have it. The privation is real and the suffering it causes is real. Of course, there are times when we experience suffering merely because we are deprived of something we want. But that is not the kind of suffering that “the problem of evil” is about.

Childhood Cancer

Having introduced the general problem of evil, let us now consider the specific case of childhood cancer as an evil.

Cancer is the uncontrolled and inappropriate replication of a genetically abnormal cell. A cancer starts as a single cell that has acquired DNA mutations that lead it into continuous replication that is not controlled by the normal signals that instruct the cell to cease self-replication. Many tissues in the body go through periods of rapid self-replication physiologically. For example, when skin is damaged the stem cells of the skin proliferate. The progeny cells derived from the stem cells then differentiate into the various types of more specialized cells needed to repair the damaged skin, ultimately becoming mature skin cells. When the skin is healed, inhibitory signals feed back on the process and the stem cells and incompletely differentiated progeny cells stop proliferating. In contrast, in a skin cancer the stem cells keep proliferating and the progeny cells do not mature into normal skin cells.

Cancers are poor guests in the body. They proliferate and ultimately destroy the host organ in which they arise. Many cancers also have the property of sending out cancer cells through the blood or lymphatic system, a property called metastatic potential. They can travel through the body and take root in other organs. There they replicate and ultimately destroy the organ they have colonized. If the cancer is unchecked the host of the cancer ultimately dies from organ or multiorgan failure.

Cancer is common. Roughly one in four people will at some point in their life have some type of cancer. In the US, there are about 2,000,000 new cancer cases each year. Many cancers are curable if they are discovered when they have not yet invaded surrounding tissues or metastasized to other parts of the body. However, cancers are a common cause of death. In the United States about one fifth of deaths are due to cancer.6 In the United States 40% of cancers are preventable and related to personal health habits.7 Cigarette smoking is related to 19% of cancers, obesity to 8% and excess alcohol use to 5%. The risk of cancer significantly increases with age. 88% of cancers are diagnosed in people age 50 years or older.

Cancer in children is rare.7,8 In the US, about 15,000 cases of childhood cancer are diagnosed each year; the risk of cancer in childhood is about 1 in 300. Cancer is the leading cause of death due to medical conditions for children in the US; deaths from motor vehicle accidents and firearm injuries are each more common than deaths from childhood cancer.9 Many advances in treatment of childhood cancer have been made and the cure rate is above 80%, although this ranges widely depending on the type of cancer.

The most common malignancies in adults are breast, prostate, lung and colorectal cancers. Children do not get these cancers. The most common childhood cancers are acute leukemias, brain tumors and lymphomas.10 Unlike cancers in adults, childhood cancers are not preventable or attributable to bad personal or family health habits. As will be discussed below childhood cancers are due to random acquired gene mutations.

The most common form of childhood cancer is acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). It represents about 25% of all childhood cancer. It is a cancer of blood forming cells in the bone marrow. It arises from a blood stem cell that has partially committed to become a lymphocyte (one type of infection fighting white blood cell). As ALL grows in the bone marrow it cripples the normal marrow and the patient develops severe anemia from the lack of normal red blood cells, bleeding from the lack of normal platelets, and severe infections from the lack of normal infection fighting cells. Intensive chemotherapy that continues for two years cures about 85% of children with ALL. The therapy is very tough.

Acquired mutations in stem-like cells cause cancer

Understanding the cause of ALL requires some understanding of normal blood development. Within our bone marrow we have relatively rare blood stem cells that have the potential to give rise to all types of mature blood cells: red blood cells, platelets, and white blood cells. These stem cells respond to molecular signals in the marrow microenvironment to temporarily transition from a dormant state to an active state in which they will reproduce. As they reproduce some undergo more molecular signaling to commit their further development to a particular class of blood cells, e.g., infection-fighting white blood cells. These initially committed cells as they continue to reproduce also respond to other signals to further commit to even more specialized cells, e.g., lymphocytes as one type of white blood cell. The process continues until the mature, specialized blood cell is formed. In general, the mature, specialized cells no longer have the capacity to reproduce. The mature cells leave the marrow and go to work in the blood and body. The bone marrow is a very busy factory. More than 100 billion blood cells are made every day in each human.

The making of blood cells generally works very efficiently. However, very rarely, random molecular accidents occur in the process of cell replication creating mutations in the genes of the blood stem cells or blood progenitor cells. Mutations are changes in the chemical sequence of DNA in the progeny cell that were not present in the original DNA sequence of the progenitor cell. Mutations range from single substitutions of one nucleic acid base, to loss of a series of bases, to flipped or inverted sequences, to loss of big chunks of DNA in a chromosome, to losses or duplications of entire chromosomes. Depending on the gene or genes impacted, the results can range from no effect, to cell death, to loss of normal function, and sometimes failure to properly control cell reproduction. Once a mutation has occurred all descendants of the mutant cell inherit the mutation. The descendants can acquire additional mutations as they replicate.

A large number of different mutations have been found among patients with ALL’s and the aggressiveness and curability are associated with the specific mutations in a patient’s leukemia.11 We can look at two examples.

The ETV6::RUNX1 mutation is among the most common mutations in ALL. It is an abnormal fusion of the ETV6 gene and the RUNX1 gene. Individually, each gene encodes a transcription factor that has a major impact on the differentiation and growth of blood cells. The abnormal fusion protein interferes with the normal orderly differentiation of blood forming cells. No one knows exactly how the mutation occurs but in many cases it occurs very early in life, even when the baby is still in the womb. The mutation by itself does not produce leukemia but sets up the cell to fully transform to leukemia as the progeny of the initial mutant cell acquires additional mutations. The ETV6::RUNX1 mutation is often associated with a good response to chemotherapy and a high cure rate.

The BCR::ABL1 mutation is less commonly found in ALL but is a bad actor. It is associated with aggressive leukemia behavior and a much lower cure rate. ABL1 is a gene that encodes a tyrosine kinase that affects many cell processes including cell division, cell adhesion, differentiation and response to cellular stress. The function of the normal BCR is not known. However, the mutant fusion gene BCR::ABL1 produces an unregulated tyrosine kinase protein that contributes to the immortality of the leukemia cell.

As noted above, more than 100 billion blood cells are made each day. This requires nearly the same number of blood cell replications that successfully and with full fidelity perfectly reproduce the DNA of the cell. Each cell’s DNA is composed of about 6 billion nucleotides that are linked together to create the cell’s chromosomes. Thus every day successful blood production requires about 600 billion billion accurate DNA synthesis reactions. This is an astonishingly large number and a huge demand for quality control.

The cell has a number of molecular mechanisms to repair errors in DNA replication.12 Hundreds of human genes have been identified as being involved in DNA repair. Defects in DNA repair mechanisms allow mutations to be propagated, and these lead to increased chance of cancer. Examples of defective DNA repair syndromes include BLM abnormalities (Bloom syndrome), BRCA1 abnormalities (breast and ovarian cancer), XPA and XPC abnormalities (xeroderma pigmentosa) and ATM abnormalities (ataxia telangiectasia).

Sometimes errors in DNA replication cannot be repaired. The cell also has mechanisms to eliminate cells with unrepairable DNA errors. The most well known process is the one mediated by the TP53 gene (TP53 stands for “tumor protein 53”). It has been dubbed “the guardian of the genome.” Working with other genes TP53 can lead to elimination of cells with unrepairable DNA damage. It triggers a process called apoptosis, or programmed cell death. The defective cell quietly dies without damaging its normal neighbors. Germline defects in the TP53 gene are associated high rates of cancer; the Li Fraumeni syndrome is an example. Patients with Li Fraumeni syndrome are at very high risk of soft tissue and bone cancers, breast cancer, and brain cancers among others. In addition, nongermline cells can acquire TP53 mutations. Cancer cells that have acquired mutations in TP53 are more aggressive and are often resistant to cancer therapies.

These DNA protection mechanisms are thought to be more than 99.9% efficient. Nonetheless, given the enormous number of chemical reactions that need to occur perfectly with each cell replication, there are still numerous cells that acquire mutations that then are passed to descendant cells. Eventually enough mutations accumulate in a cell as it goes through multiple rounds of replication and it is transformed into a cancer cell. Sometimes this occurs in a child and that child gets cancer.

After reflection on the complexity of cell replication one response is awe. Many feel deep amazement that any cell can replicate itself with complete fidelity, let alone have this process occur more than 100 billion times a day. Others may react differently. Why does not God produce a completely error-free process for cell replication? God is all powerful and all knowing. Should not God do a lot better?

What if God did a lot better than 99.9%? Let us imagine that DNA replication was 100% accurate. Mutations would not occur in cells in our bodies as they developed from the fertilized ovum and produced our bodies. Cancers would not develop. No children would ever suffer from cancer.

Unfortunately, there would be no children on planet Earth. Why?

The molecular origin of life remains shrouded in mystery. The origin of the first living cell remains unknown. However, the genetic evidence makes clear that all life on Earth is related, and family trees of biological relatedness have been constructed. God has created a marvelous mechanism by which life has evolved over time to create the beautiful balance of unimaginably large of numbers of species, including us, Homo sapiens.

Spontaneous heritable variations in DNA of germ cells are the essential building blocks of molecular evolution in humans, other animals and plants.13,14,15,16,17 Germ cells are those cells in an organism that can give rise to new organisms. In humans, germ cells are those cells that give rise to ova and spermatozoa. An ovum fertilized by a sperm creates a new human being. Somatic cells are the rest of the cells in the body that give rise to the tissues of the body but are not involved in producing offspring. Most of the mutations in germ cells are silent and have no impact on the fitness of a new organism to prosper. Some are terrible and lead to reduced fitness and the mutation will disappear from the gene pool. Rarely, a mutation will occur that will confer a real advantage and the descendant organisms harboring it will prosper and propagate the “good” mutation. Over time, the descendants become more and more distinct, acquiring new capabilities, and a new species emerges. If DNA mutations were prevented in germ cells, no development of multicellular life would occur on Earth. Ultimately, no Homo sapiens. No children. Just lots of the primordial cells giving rise to exact copies of themselves as the eons roll by.

Well, maybe God could allow mutations to occur in germ cells but not in somatic cells. Would not that do the trick? We could keep generating variants in germ cells that would allow development of life on earth, but no cancer causing mutations in somatic cells could occur.

The problem with this line of thought is that the process of DNA replication in germ cells and somatic cells is basically the same. In fact, not all life forms have germ cells. It is reasonably speculated that unicellular organisms emerged on Earth first. It was only later in development of life on Earth that multicellular organisms emerged, and only later on from these multicellular organisms that other species that make use of germ cells emerged. So it is reasonable to conclude that the capacity for variations in DNA sequences (mutations) was itself necessary for the emergence of germ cells. It makes no sense to say once germ cells with the capacity for genetic variation developed, a completely new, error-free process for replication of somatic cells should appear.

Because random DNA changes in cell replication are required for development of life in this universe, the same process will inevitably produce cancers.

Existential responses to the problem of childhood cancer.

Let us return to St. Augustine and apply his reasoning to a nonmalignant cell and a cancer cell. Both are complex entities which exhibit amazing feats of metabolism, locomotion and self-replication. At a molecular level they are very similar. However, the cancer cell lacks the goodness of the nonmalignant cell’s capacity to stop dividing when additional cells are not needed. The cancer cell is not intrinsically evil. It does however lead to pain and the earlier demise of the person who has the cancer. This appalls us. We want a world in which there is no sickness, no death, no pain. We demand that God provide this for us.

St. Thomas Aquinas also would say that the cancer cell is not intrinsically evil, but lacks some perfections of the nonmalignant cell. While this is unassailably true, we may not want to offer this observation when we are trying to console a child or their parents in the face of a newly diagnosed cancer.

Perhaps weeks or months later we would introduce other aspects of St. Thomas’ thoughts. He noted that death is inevitable for all living things on earth. Our human bodies are not immortal. They are material things and all material things are transitory. We recoil from death, but it is an inevitable consequence of living in a material world. Many people do come to accept this as they face a fatal illness. In the stages of grief as described by Kübler-Ross, acceptance is the final stage. We do not like or understand it, but we accept it.

Scripture offers us some counsel on suffering. The Book of Job is an extended reflection on and attempt to understand unmerited suffering. In the narrative Job is a God fearing, righteous man. In the heavens God praises Job, but “the satan” says this is only because everything is going well for Job. The satan predicts that if things go badly for Job, he will curse God. God grants the satan permission to conduct this trial. Unfathomable disasters come upon Job. He does not understand his plight. His unhelpful friends tell him he must have done something terrible to account for the evil that has been visited upon him. Job denies this. In his sadness he curses the day he was born but does not curse God. However, Job requests a hearing from God. God comes in a storm and mightily tells Job that no created thing can be the judge of the Creator. In the end, Job simply accepts God’s sovereignty and will.

Pope St. John Paul II offered some thoughts on suffering in his 1984 apostolic letter entitled, Salvifici doloris.18 One English translation of this title is “saving pain.” He notes that suffering is a universal human experience and that man suffers because of evil which is a lack of, limitation of, or distortion of good; but he says that we have hope in Christ, because Christ drew close to human suffering through taking suffering upon his very self. Christ’s suffering is critical for human redemption. Because of Christ’s salvific work, man exists on earth with the hope of eternal life and holiness. Echoing St. Paul (Col 1:24), St. John Paul II says that our human suffering can participate in the suffering of Christ. By joining our pain and sorrow with Christ’s, we can become more closely conformed to Him and united to Him. And by being close to others in their sufferings, we can even be to some degree the presence of Christ for them.

Conclusion

Childhood cancer does fit Webster’s Dictionary definition of evil as something that that causes displeasure, injury, pain, or suffering. However, its presence does not mean that there is no all-powerful, all-caring and all-knowing God. In our world God has created the conditions for life to develop and for us as a species to emerge. God has not created cancers as ontologically distinct things whose purpose is to cause suffering. Cancers develop from good cells but ultimately lack some important features of good cells. Within the universe as we understand it scientifically today, it would not be possible to have human life without the possibility of cancer. This truth does not diminish the pain and deep sadness of childhood cancer. However, with prayer and grace perhaps we can approach our suffering with openness to God and ultimately join our sorrow with that of Jesus in His redemptive suffering.

[Dr. CRAIG MULLEN is a physician scientist at the University of Rochester Medical Center. His current research work examines the bone marrow microenvironment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia.]

References

- Webster’s New Twentieth Century Dictionary, Second Edition, 1983.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Problem_of_evil

- https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/augustine/#WillFree

- Augustine, Saint, Bishop of Hippo, On free choice of the will/Augustine; translated, with introduction and notes, by Thomas Williams. Hackett Publishing, 1993.

- https://aquinasonline.com/nature-of-evil/

- https://www.medicinenet.com/what_are_the_odds_of_getting_cancer/article.htm

- American Cancer Society, Cancer Facts & Figures 2025, Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2025.

- https://www.cancer.gov/types/childhood-cancers/child-adolescent-cancers-fact-sheet

- Goldstick JE, Cunningham RM, Carter PM. Current Causes of Death in Children and Adolescents in the United States New England Journal of Medicine. 2022 May 19; 386(20): 1955–1956. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2201761.

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10042524/pdf/nihms-1876628.pdf

- Brady SW, Roberts KG, Gu Z, et al.: The genomic landscape of pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nature Genetics 54: 1376-1389, 2022.

- Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, Scientific Background on the Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2015, Mechanistic Studies Of DNA Repair, Advanced information. NobelPrize.org. Nobel Prize Outreach 2025. Wed. 8 Oct 2025., https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/2015/advanced-information

- R. Herschberg, Mutation—The Engine of Evolution: Studying Mutation and Its Role in the Evolution of Bacteria, 2015, Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a018077

- Cooper DN, Human gene mutation in pathology and evolution, J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 25:157-182, 2002.

- Loewe L and Hill WG. The population genetics of mutations: good, bad and indifferent. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B (2010) 365, 1153–1167, doi:10.1098/rstb.2009.0317

- Ohno M. Spontaneous de novo germline mutations in humans and mice: rates, spectra, causes and consequences. Genes Genet. Syst. (2019) 94, p. 13–22.

- Catarina D. Campbell and Evan E. Eichler. Properties and rates of germline mutations in humans. Trends in Genetics, 29:575-584. 2013.

- https://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/apost_letters/1984/documents/hf_jp-ii_apl_11021984_salvifici-doloris.html