God and Extraterrestrials

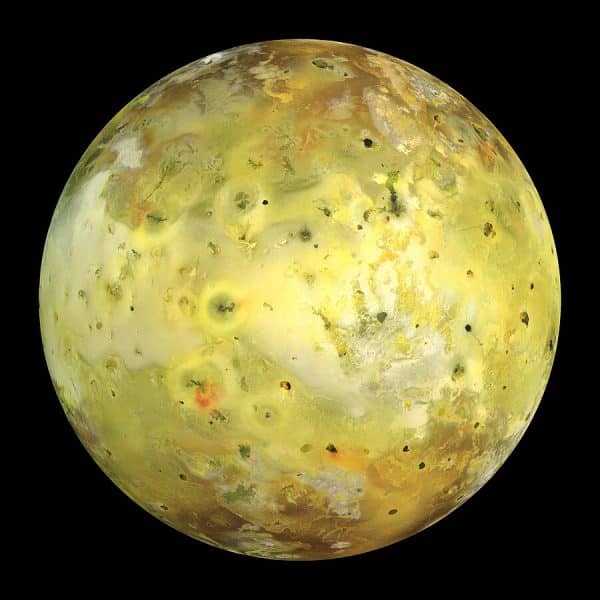

Above: Jupiter’s moon Io. NASA’s Galileo spacecraft acquired its highest resolution images of Jupiter’s moon Io on 3 July 1999 during its closest pass to Io since orbit insertion in late 1995. This color mosaic uses the near-infrared, green and violet filters (slightly more than the visible range) of the spacecraft’s camera and approximates what the human eye would see. [copyright information at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Io_highest_resolution_true_color.jpg]

The discovery of numerous exoplanets, some seemingly habitable, and rumors and claims about UFOs have piqued public interest in the possibility of intelligent extraterrestrial life. In this article, I will discuss four questions: (1) How likely is it that intelligent ETs exist? (2) How likely is it that they have ever visited earth or that humans will ever encounter them? (3) Would the existence of intelligent ETs conflict with Catholic belief? And (4) how might such beings be redeemed, if indeed they exist and stand in need of redemption?

How likely is it that intelligent ETs exist?

The answer to this question is that no one knows. We cannot assert that it is likely, nor can we assert that it is unlikely. There is simply no way to estimate the probability. It depends on two unknown factors: (a) the number of habitable planets, and (b) the probability that on a typical habitable planet intelligent life would evolve. About the first factor, one can only give a lower bound, because we only have information about the part of the universe that is within our cosmic “horizon,” i.e. the part from which light has had time to reach us since the Big Bang. Within this so-called “observable universe,” which is tens of billions of light-years across, there are roughly 1022 stars; and it is thought that a substantial fraction of them have habitable planets, based on what recent exoplanet research has shown. But there are very strong theoretical reasons to believe that the entire universe is exponentially larger than the observable part. (This would explain the remarkable “flatness” of the spatial geometry of the observable part. An analogy is that the Earth’s surface appears flat if you can only see a small part of it.1) In fact, in the standard Big Bang theory, the universe can be of infinite spatial volume, and nothing we know at present proves that it is not.2 Therefore, all we can say, and probably ever will be able to say, is that the number of habitable planets is at least 1022, probably exponentially larger than that, and possibly infinite.

As far as the second factor, the probability of highly intelligent life evolving on a typical habitable planet, we only know that it is not zero, because we exist. It could be, however, exponentially small. For example, there could be some hurdles on the road to intelligent life that it is very difficult for evolution to surmount. One such hurdle might be the formation of the first living and self-reproducing one-celled organism. A second might be the making of eukaryotic cells (cells with nuclei) from simpler prokaryotic cells. A third might be making multicellular organisms — on Earth that step took several billion years. Another might be developing high intelligence. Suppose (using round numbers for the sake of illustration) that there were five such high hurdles and that the chance of evolution surmounting each of them on a typical habitable planet was one in a thousand. Then the chance of surmounting all of them would be (1/1000) raised to the fifth power or 10-15. Because the probabilities of getting over multiple hurdles get multiplied, one sees that the chances of highly intelligent life evolving on a typical habitable planet could be exponentially small — though it might not be.

So the statistically “expected” number of planets in the universe with highly intelligent life is some exponentially large number times some number which could be exponentially small, where the exponent in each case is unknown to us. The answer, therefore, could be anything. If it is very small compared to one, it would mean that our existence is an amazing statistical fluke, and that we are almost certainly alone in the universe. If it is very large compared to one, then almost certainly there are a vast number of intelligent species scattered throughout the universe. Could the answer come out in between, say a number like 2 or 3? That would be very strange, as it would require that the large number of habitable planets and the small probability per habitable planet closely counterbalance each other, which they have no reason to do. In short, if there are intelligent extraterrestrials at all, it seems most likely that a vast number of planets have them rather than just a few. And, as we will see, that has some bearing on some theological questions.

How likely is it that humans and rational ETs have met or will ever meet?

There has been a lot of hoopla in the press recently about UFOs (or UAPs as they have been rebranded). Whatever UFOs are, it seems extremely unlikely from a scientific standpoint that ETs have ever visited us humans or ever will. There are two reasons for this. The first is that faster-than-light (or FTL) travel is almost certainly impossible in light of what is presently known about fundamental physics. It is easily shown on the basis of Special Relativity that if FTL travel were possible then time travel would also be, and that would lead to bizarre “temporal paradoxes” 3 (such as the famous “grandfather paradox,” in which a person travels back in time and prevents his own parents from being born). While the equations of General Relativity seem to allow the hypothetical possibility of “traversable wormholes” 4 in spacetime, which would permit both time travel and FTL travel, the formation of such wormholes would require the existence of negative-energy matter that does not exist in the real world. The impossibility of FTL travel means that any ETs who wanted to make a round trip to Earth would have to be from a planet very close to us. And the number of habitable planets within, say, forty light years of Earth is only in the tens, not hundreds, let alone 1022.

The second reason that alien visitations are extremely unlikely is that even if an intelligent species were to evolve on a planet of a nearby star the probability that they would exist at the same time as humans do in the history of the cosmos would seem to be utterly negligible. Our species has been around for about 200,000 years, which sounds like a lot but is a blink of an eye in comparison to the 14 billion years of cosmic history. It is vastly more likely that we and any given species of intelligent ETs would miss each other by hundreds of millions of years than that we would overlap in time. So, the idea that any humans have encountered ETs or ever will is quite far-fetched, even if theoretically possible.

However, even though the existence of intelligent extraterrestrials will probably always remain in the realm of pure speculation, it is important to reflect on it theologically. For, given what we know, intelligent ETs might well exist, and surveys indicate that a large fraction of the general public believes that they do. Therefore, it is a pastorally important question whether the existence of such beings would be consistent with the Catholic faith.

Would the existence of intelligent alien species be contrary to the Catholic faith?

It is important to clarify that what is at issue here is not “intelligence” in the sense that one might talk about a dog or dolphin being intelligent. Many terrestrial creatures have intelligence of that sort, and no one has ever imagined this to be theologically problematic. Rather, one is talking about what in Catholic tradition is called “intellect” or “rationality,” which is conceived of as a spiritual power.5 Even in this regard one must remember that angels are traditionally taught to be purely intellectual, spiritual beings, and their existence is not only unproblematic theologically, but an article of faith. What is specifically at issue, then, is the existence elsewhere in the physical universe of other embodied creatures who possess rationality — and thus also free will — and who would therefore possess “immortal spiritual souls” and be made in the “image of God.” For clarity, let us call such hypothetical creatures “rational extraterrestrials.” Of course, by Catholic teaching, if such beings do exist, they are not purely the result of an evolutionary process, since their rational souls would be “directly” created by God.6

Now, certainly it is the case that the existence of such rational extraterrestrial species is nowhere mentioned in Scripture and does not seem even to have been contemplated by any of the scriptural writers. Therefore, it would be out of place to read into scriptural verses answers to questions about ET life that their authors did not ask themselves. That would be to commit what one theologian (in another context) has aptly called “the fallacy of the unasked question.” For example, when St. Paul says in Philippians 2:10-11 that “at the name of Jesus every knee should bow, of those in heaven, and of those on earth, and of those under the earth,” he doubtless was thinking of the blessed in heaven rather than space aliens.

The question naturally arises whether one would expect Scripture to mention ETs, if they do exist. It is hard to see why one would. There are many aspects of the universe that Scripture is silent about, including the very existence of planets outside the solar system, the vast size of the universe, and its immense age. It is also silent about the existence of many kinds of terrestrial life, including dinosaurs. Even on many matters that are important in a practical sense, Scripture tells us nothing, whether it be electricity, or agriculture, or medicine. God has left it to human reason, effort, and responsibility to learn about this world and how to make our way in it. Scripture is not about Nature and its secrets,7 but about God and mankind’s relationship to him, as well as our relationship to each other. For reasons mentioned in the previous section, the human race is extremely unlikely ever to encounter rational extraterrestrials, and so they are not a part of the story of mankind and its redemption. Nor would we humans be part of their story or their “salvation history.”

Even though there is no obvious reason why God would reveal anything to us about rational extraterrestrials, there also is no obvious reason why he would not create them, and some reasons to think he might. Generally, a composer does not create just one work, a novelist just one novel, or a poet just one poem. And God is not stingy with his love. After all, the human race itself comprises many tens of billions of individuals, and God does not love any of them any less for that.

In fact, Christians have been speculating for centuries about life elsewhere in the universe, and the prevailing view seems to have been that it is more in accord with God’s generosity and munificence to have created life all throughout the universe.8 Some even suggested a “principle of plenitude,” according to which the universe should be as full of life as possible. There is nothing in Christian tradition or teaching that militates against the possibility that rational ET life exists and perhaps in great abundance. Where things get trickier is with the question of how such beings would be saved.

How would rational ETs be saved?

The first question to consider is whether ETs, if they exist, stand in need of redemption. Perhaps all rational ETs species are unfallen, as are those in C.S. Lewis’s Space Trilogy. However, if the number of rational species in the universe is exponentially large — which is the most likely case if ETs exist at all — it would be an astonishing coincidence if only we humans were fallen. The problem lies not in the notion that only one rational species has fallen, but rather with the idea that we would happen to be that one. So if rational ET species exist, it seems most likely that many of them, if not all, are fallen and stand in need of redemption. The question is how God would save them.9

There are two theories. One is that all rational embodied creatures throughout the universe would be saved through the unique and unrepeatable sacrifice of Jesus of Nazareth on a cross on Calvary two thousand years ago. The other is that God the Son would have multiple Incarnations, taking the forms (or in the traditional terminology “assuming the natures”) of every kind of rational embodied species in the universe, or at least those that had fallen. (Though here one must note that some of the Church Fathers as well as later theologians held that God would have become incarnate as a man even had humanity not fallen.10)

Of course, we do not know which of these theories is correct (if there are rational ETs), as God has not revealed anything about it, and consequently there is no Catholic teaching on the matter. One is in the realm of free speculation. That has not stopped theologians from having strong opinions. (I vividly recall the vehement negative reaction of a friend of mine, who was a Jesuit theologian of considerable reputation, when I broached the topic of multiple Incarnations to him some years ago.) Opinion, however, is divided among Catholic theologians who have considered the question.

There seem to be three main arguments given by proponents of the single-Incarnation theory. First, if the sacrifice of Christ on Calvary can be the means of salvation for human beings who lived before the time of Christ and for those who have lived since but have never heard of Christ, why could it not also be the means by which ETs are saved? Second, there are a number of scriptural verses that suggest a cosmic scope to Christ’s salvific work and others that state that there is just a single mediator of salvation; though, as we will see, these do not necessarily prove the single-Incarnation theory. And, third, the very notion of multiple Incarnations seems problematic and even scandalous to some, as for example the Jesuit friend I referred to.

The first argument is quite logical, but its plausibility would be diminished in two ways if the number of planets with rational ET life is exponentially large. For while it might not be surprising that an Incarnation would happen on only one planet, it would be surprising if that one just happened to be ours. Moreover, it would be making the exception into the rule. It is true that there have existed many human beings — tens of billions, in fact — who never heard of Christ; but it is likely that by the end of human history a majority of all humans who will have ever lived will have heard of him, assuming that the human race carries on for at least a few more centuries and the gospel continues to be preached. So, one can regard those human beings who never heard of Christ but were nonetheless saved as exceptions to the rule. But if there are, say, trillions of rational ET species throughout the universe, and there is only the one Incarnation here on Earth, then the embodied rational beings who will never have heard of Christ would vastly outnumber those who will have. In that case, being saved by hearing “Christ crucified” preached would not be the rule, but rather the very rare exception. That would be analogous to the salvation of the human race being accomplished through an Incarnation that happened on some remote South Sea island with a population of only a few people, who witnessed the life, death, and resurrection of the Son of God and were then wiped out by a tsunami, leaving the rest of humanity completely unaware that the Incarnation had ever happened. That would be a strange “plan of salvation,” especially as it seems that Christ wanted the human race to learn of his mission, given that he commanded his disciples to “baptize all nations.”

Having looked at the single-Incarnation theory, let us see what can be said for and against the alternative.

Multiple Incarnations?

For many people, no doubt, the idea of multiple Incarnations is so strange as to seem absurd or even impious. However, so great a theologian as St. Thomas Aquinas did not regard it as such. Of course, he was not thinking of extraterrestrials, but of multiple human Incarnations of the Son of God. He posed the question, in Summa Theologiae, Part iii, question 3, article 7, “Whether One Divine Person Can Assume Two Human Natures.” His answer was yes. In fact, St. Thomas argued that the Son of God is able in principle to assume numerous distinct human natures, in the sense that it would be neither logically nor metaphysically impossible for him to do so. And, if that is the case, then it would seem also to be possible for the Son of God to assume the natures of a multiplicity of different rational species.

I will return in the last section to the question of whether and how this makes metaphysical sense. But first let us examine the question why multiple Incarnations might make sense as a means of saving extraterrestrials, if they exist. There are at least three interconnected reasons why it would.

The first reason has to do with the connection between the Incarnation of Christ and the Fall of Man. Christ, the “last Adam” or “second Adam” (1 Cor 15: 45-47), came to undo what had been done by the “first Adam.” By Catholic teaching, the first human beings had enjoyed a friendship with God and certain graces and “preternatural gifts,” which by turning away from God they forfeited for themselves and their descendants — that is, for the human race. And only the human race, not any ET races that there might be; for the effects of that primordial Fall, according to the Council of Trent, are passed on “by propagation.” If the work of the “second Adam,” Christ, is to repair the damage done by the first, it would seem that it is to spiritually heal the human race, and only the human race, and restore it to friendship with God.

This leads us directly to the second reason, which is a theological principle enunciated by many of the Fathers of the Early Church, namely that “what has not been assumed cannot be healed.” 11 Human nature, which had been wounded by the transgression of our “first parents,” can only be healed if that nature is “assumed” by the Son of God, i.e. taken up into himself in the Incarnation. This principle was used to answer those in the early centuries of Christianity who argued that Christ was not fully human — that he lacked, for example, a truly human body or a human soul. It was answered that if he did not possess humanity fully then humanity would not be redeemed fully. That is why, in the words of the Letter to the Hebrews, Christ had to be a “man like us in all things but sin.” But if we generalize this principle it would appear that the nature of a rational ET species, if wounded by sin, could not be healed unless that ET nature were assumed into the Son of God as well. Their redeemer must be like them in all things but sin. In 1 Timothy 2:5, one reads, “For there is one God, and one mediator between God and man, the man Christ Jesus.” Here again we see it emphasized that the mediator shares the nature of those whose relationship to God he mediates.

And this brings us to a third and most fundamental point. Some who discuss the Incarnation seem to conceive of it as merely a means to an end, salvation. However, it is not just the means to salvation, but the very substance of salvation. Salvation is not merely the avoidance of punishment or perdition, nor is it merely traveling to Heaven conceived of as a place; rather it is total union with God. God desired to unite humanity to himself in an intimate and indeed “nuptial” union.12 This nuptial union is both spiritual and corporeal. It began in the Incarnation of Jesus Christ, who in himself unites the divine and human; but others were to be brought into this union by becoming joined to Christ as members of his Body, the Church, which is Christ’s body in a quite literal sense (though not a “biological” sense). Thus, being members of this Body as it will be in its glorified state, and intimately united thereby with God and with each other, is the substance of being “in Heaven.” The Body of Christ, when it reaches its ultimate completion on the “last Day” will be the “whole Christ” (or “totus Christus”), in which God and Man achieve that definitive union. That is what Heaven is. That is why Joseph Ratzinger in his book Eschatology wrote,

“The perfecting of the Lord’s body in the pleroma of the “whole Christ” brings heaven to its true cosmic completion. Let us say it once more before we end: the individual’s salvation is whole and entire only when the salvation of the cosmos and all the elect has come to full fruition. For the redeemed are not simply adjacent to each other in heaven. Rather, in their being together as the one Christ, they are heaven.” 13

When one recognizes this, one sees that Incarnation is not just one good way among others for God to save his creatures, it is the very substance of the salvation and the life he offers. Indeed, this is why some of the early Church Fathers said that God would have become Incarnate as a man even if man had not sinned.

[Incidentally, this perspective sheds light on what some regard as a “hard saying” of the Church’s tradition, namely that “extra ecclesiam nulla salus” 14 (“outside the Church there is no salvation”). The Church has explained that this does not mean that all human beings who never heard of Christ in this life or who never received baptism cannot be saved. But it does mean that those of them who are saved and end up in heaven, also by definition end up in the “totus Christus,” the Body of Christ, the “Church Triumphant.” So, in the end, they will not be “extra ecclesiam.”]

So, applying all this to other rational species that might exist elsewhere in the universe, it suggests that if any such species is to be redeemed it would be through an Incarnation by which that species, its nature, and its members collectively and as individuals are united to the Son of God.

Now, if this is true, it would lead to some corollaries. More than one Incarnation would imply more than one Body of Christ — as many as there are rational species whose natures God assumed. And perhaps one should also say, therefore, as many “Heavens.” The human race had an original unity with itself and with God that was shattered by sin. In the human Body of Christ, when it achieves completion, that unity will be restored. But there was no original unity of the human race with ET rational species (if they exist), except, of course, that all rational species have their origin in God. So, while all rational creatures in this universe who are redeemed will be united to God in his Son, we do not know whether they will be united in a single Body with those of other rational species.

And finally we come to an absolutely vital point. Even if, hypothetically, there were multiple Incarnations of the eternal Son of God, the Second Person of the Blessed Trinity, they would all be Incarnations of one and the same divine Person. While, as St. Paul wrote, our knees must bend “at the name of Jesus,” it may be that those in other parts of the universe bend their knees (or make whatever the analogous bodily gesture would be) at a different-sounding name, but not the name of a different Person. It would be the name of the same Son of God as he came among them and “dwelt among them” as one like them “in all things but sin.” And if the Son of God undergoes rejection, suffering and death on multiple planets, it would be the same divine Person undergoing them in every case. It would be one and the same eternal decision on the part of that divine Person to humble himself and offer himself for all his children. It is that eternal decision of the Son of God that is referred to in Revelation 13:8, which speaks of the “Lamb slain from the foundation of the world.” Similarly, 1 Peter 19-20 refers to “the precious blood of Christ, as of a lamb without blemish and without spot, who verily was foreordained before the foundation of the world, but was manifest in these last times for you.” That one and only Lamb was manifest for us humans as Jesus Christ, but perhaps could be manifest in a different form for other rational species. Therefore, it can be argued that scriptural passages that emphasize a single sacrifice and a single mediator and passages that imply a cosmic dimension to Christ’s sacrifice do not have to be interpreted to exclude multiple Incarnations.

Would multiple Incarnations make metaphysical sense?

Before getting to that question, one must review how it is that the human Incarnation of the Son of God makes metaphysical sense. It raises some very puzzling questions that were much debated in the early Church. At first it seems like a contradiction in terms. How can the same Christ be both God and man, if God is infinite and man is finite? If Jesus of Nazareth is human, then as a human his thoughts, emotions, and sensations would change from moment to moment and his memory would have finite capacity. He would be capable of forgetting and of learning. Hebrews 5:8 tells us he “learned obedience by what he suffered.” Luke 2:52 says that “he grew in wisdom.” On the other hand, if Jesus of Nazareth is God, then as God his mind is infinite and unchanging, and he knows all things in one timeless act of understanding. To resolve the puzzle, some denied his full humanity, saying that it was swallowed up in his divinity, or that he only appeared human. Others denied that he was fully God, saying that he was only an exalted creature, or that while on earth he laid aside his divinity. But all of these were false solutions and dead ends. They were contrary to both Scripture and Apostolic Tradition and were condemned by a series of Ecumenical Councils. The Church resolved the apparent contradiction in a different way that accorded with both Scripture and Apostolic Tradition, by teaching that Christ, though “one Person,” has “two natures,” a divine nature and a human nature, and therefore must have two minds and two wills. He has both a divine intellect and a human intellect; he has both a divine will and a human will; and so on. (Those who denied that Christ had two wills were called “monothelites,” or one-willers, and monothelitism was condemned by the Third Council of Constantinople in 680-1 AD.15)

This resolves the apparent contradiction, but not, of course, the mystery. How can one person have two minds? We, who have only a human nature, obviously cannot imagine it. But perhaps we can make the mystery seem a bit less strange by an analogy, taken from the Athanasian Creed, a doctrinal statement dating to about the late 5th century. That creed makes an analogy between the union of the divine and human natures in Christ and the union within a human being of the spiritual soul and the body:

“For as the rational soul and flesh is one man, so God and Man is one Christ.”

Let us push this analogy further. The “one Christ” is both God and Man, and so he has two ways of knowing, through his divine Intellect and through his human intellect. In a human being, there is both the “rational soul” and “flesh,” and, correspondingly, a human being has two ways of knowing: namely through rational intellectual knowledge and through the bodily senses. And so even we who are just human, experience having two quite disparate modes of knowledge. In fact, the analogy can be pushed further still. Ordinarily, what I know through the bodily senses I also know rationally; but I know many things rationally that my senses cannot. Thus, for example, my reason knows that I am feeling pain or having the sensation of warmth or seeing the color red. But my senses cannot know most truths that are grasped by my reason, such as, for example, moral truths and mathematical truths. By analogy, Christ’s divine Intellect knows all things, including what his human mind knows; but his human mind, being finite, cannot know everything grasped by his divine Intellect. Of course, any analogy between created things and God must be extremely inadequate. We should not push them too far, but they can be useful.

As the foregoing analogy can help us see how the Incarnation of the Son of God as a man does not involve a contradiction, it can also help us understand how multiple Incarnations might also be consistent. A human being does not just have two modes of knowing, the rational and the sensory, but many: namely the rational and several bodily senses. Moreover, while what is known by the reason encompasses (generally) what is known by all the senses, each sense is ignorant of most of what the reason knows as well as what is known by all the other senses. My sense of sight does not know sounds, nor my sense of hearing know smells, for instance. The analogy would be that the Son of God would know in his divine Intellect all that is known through his many assumed natures, but each assumed nature would be ignorant of most of what the divine Intellect knew as well as what all the other assumed natures knew (unless by supernaturally “infused knowledge”).

Of course, all this is at the extreme limit of speculation. And the analogy made in the Athanasian Creed is, like all analogies, imperfect. Nevertheless, it may help at least to make the idea of multiple Incarnations seem less problematic.

Conclusion

We do not know whether rational ETs exist or have existed or will exist. We do not even know enough to say whether their existence is probable or improbable, scientifically speaking. In any case, it is highly unlikely that we will ever encounter them. Nevertheless, their possible existence raises theological questions that many wonder about. There seems to be no conflict between the existence of such beings and anything Christianity teaches. Indeed, many Catholics and other Christians have argued over the centuries that if the universe can harbor such life one might expect such life to exist in abundance, because of God’s boundless creativity and generosity. We do not know whether such beings, if they exist, would require redemption, or how God would choose to redeem them. But there seem to be good reasons to suppose that it would be by God dwelling among them as one like them, as he “dwelt among us” as “one like us.” But as the Church has taught nothing about all these possibilities, one is at present free to weigh the evidence and arguments and form one’s own conclusions.

References

1. One of the major theoretical puzzles in cosmology (called “the Flatness Problem”) is that the three-dimensional space of the universe on cosmic scales is very flat, i.e. approximately Euclidean. (For example, the angles in a triangle would add up to approximately 180 degrees.) It is believed that the explanation of this is that shortly after the Big Bang the universe underwent a sudden and extremely rapid expansion by many orders of magnitude (called “cosmic inflation”) which stretched and flattened space, the way inflating a balloon flattens it surface.

2. A common misconception is that the finite age of the universe would imply a finite size. But in the standard Big Bang theory, the universe can have either an “open geometry” with negative (or zero) spatial curvature and infinite volume, or a “closed geometry” with positive spatial curvature and finite volume. Since the spatial curvature is so close to zero (i.e. “flat”), we cannot presently tell whether the universe is open or closed, and may never be able to tell.

3. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Temporal_paradox

4. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wormhole

5. Catechism of the Catholic Church, par. 1705.

6. Catechism of the Catholic Church, par. 366.

7. “[T]he sacred authors … did not attempt to penetrate the secrets of nature …” Encyclical Letter Providentissimus deus of Pope Leo XIII (Nov 18, 1893), par. 18. https://www.vatican.va/content/leo-xiii/en/encyclicals/documents/hf_l-xiii_enc_18111893_providentissimus-deus.html

8. See the article “Extraterrestrial Intelligence and the Catholic Faith: a brief history of an ancient conversation”, by Paul Thigpen, on the SCS website https://catholicscientists.org/articles/extraterrestrial-intelligence-and-the-catholic-faith-a-brief-history-of-an-ancient-conversation/ For more detail see Extraterrestrial Intelligence and the Catholic Faith, Paul Thigpen (TAN Books, 2022), chapters 1-9.

9. This has been much discussed in recent years. See, for example, Christianity and Extraterrestrials: A Catholic Perspective, Marie I. George (iUniverse, 2005), ch 1; Vast Universe: Extraterrestrials and Christian Revelation, Thomas F. O’Meara (Liturgical Press, 2012), ch 4; and Extraterrestrial Intelligence and the Catholic Faith, Paul Thigpen (TAN Books, 2022), chs 12-13.

10. In Summa Theologiae, Part iii, question 1, article 2, St. Thomas Aquinas notes, “There are different opinions about this question. For some say that even if man had not sinned, the Son of Man would have become incarnate.”

11. Statements of this principle by many of the early Church Fathers can be found in The Faith of the Early Fathers, tr. William A. Jurgens (Collegeville, MN; Liturgical Press, 1970). For example: St. Irenaeus: “He united man with God. For if man had not conquered the enemy of man, the foe would not have been rightly vanquished.” / St. Athanasius: “Rather, the Savior having in truth become man, the salvation of the whole man was accomplished.” Vol. I, par. 794. / St. Cyril of Jerusalem: “For if Christ is God, as indeed He is, but took not human nature upon Him, then our estate is as strangers to salvation.” Vol. I, par. 827. / St. Basil the Great: “If the coming of the Lord in the flesh did not take place, … [then] we who had been dying in Adam would not have been made alive in Christ, that which had fallen apart would not have been repaired, …” Vol. II, par. 928. / St. Gregory of Nazianz: “That which was not assumed has not been healed; but that which is united to God, the same is saved.” Vol. II, par. 1018. / St. Ambrose: “Because He came, therefore, to save and redeem the whole man, it follows that He took upon Himself the whole man, and that his humanity was perfect.” Vol. II, par. 1254. / St. Cyril of Alexandria: “For if he had not been born like us according to flesh, if he had not communed on an equal basis in what pertained to us, He would not have absolved the nature of man from the crimes contracted in Adam.” Vol. III, par. 2128.

12. Catechism of the Catholic Church, par. 1612.

13. Joseph Ratzinger, Eschatology: Death and Eternal Life, 2nd edition, tr. Michael Waldstein, ed. Aidan Nichols, O.P. (Catholic University of America Press, 1988), p. 238.

14. Catechism of the Catholic Church, par. 846.

15. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monothelitism