The New Scopes-Trial Myth: Eugenics and Evolution at Dayton

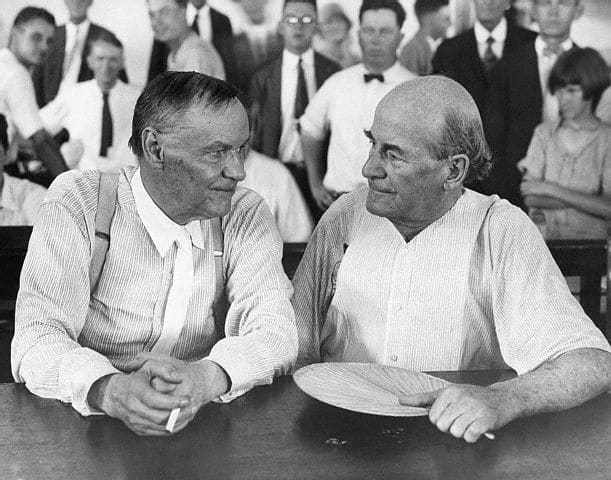

Above: Photo taken of Clarence Darrow (left) and William Jennings Bryan (right) during the Scopes Trial in 1925. [Copyright information can be found at [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scopes_trial#/media/File:Scopes_trial.jpg]

1. The Scopes Trial: Its History

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the infamous Scopes Trial, also known to many as the “Monkey Trial.” Along with the trial of Galileo three centuries earlier, it has done much to shape popular impressions of the historical relation of science and religion. This is largely due to the fact that the actual events of the Scopes trial, like those of the Galileo case, became encrusted in the public imagination with much mythology. There are actually two mythical versions of the Scopes Trial. In the old and familiar Monkey Trial myth, it was the defense that held the moral high ground. In the myth that is now developing, it was the prosecution. As usual, however, the actual history is both more complex and more interesting than the myths surrounding it.

The trial, The State of Tennessee vs. John Thomas Scopes, was the product of three events.

First, was the campaign by the American populist-progressive politician William Jennings Bryan to prohibit the teaching in public schools of man’s evolution from animals. This had born fruit in Tennessee’s Butler Act, signed into law in 1925.

Second, was the decision by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) to challenge the statute, which it saw as inconsistent with the freedom of teachers and a violation of constitutionally protected civil liberties. In order to challenge the law’s constitutionality in court, the ACLU needed not only a case, but also a conviction that they could appeal.

Third, was the eagerness of some of the leading citizens of Dayton, Tennessee, including lawyers and public-school officials, to host a test case in their city. They were able to persuade a local teacher, John T. Scopes, to agree to be charged with having taught evolution in the city’s schools.

The outcome of the trial was a conviction, as Scopes’s attorneys needed for their larger legal strategy, and as they conceded that the evidence required. However, as it turned out, the conviction was overturned on a technicality by the Tennessee Supreme Court, and the Butler Act remained on the books until its repeal by the state legislature in 1967.

The trial has since become, in the words of Joseph Wood Krutch, who had covered it for The Nation in 1925, part of “the folklore of liberalism.”1 It was helped along in this role by Jerome Lawrence and Robert E. Lee’s 1955 play Inherit the Wind and its 1960 film version, which etched into public consciousness an historically incorrect image of Scopes as a courageous schoolteacher persecuted for teaching evolution in his classroom by the religious fanatics who inhabit the Bible Belt. This despite the playwrights’ explicit denial that their play is a history of the Scopes Trial. Lawrence even denied that the play is about the relation between science and religion.2

2. The Old Scopes-Trial Myth

Five years ago, I devoted a chapter of my book The War That Never Was3 to arguing against what I will now call the Old Scopes-Trial Myth, the idea that the trial (and the larger Bryan Campaign) was just one battle in a larger war between science and religion. In that book, I showed that the “war” underlying the Scopes Trial was in fact not one between science and religion, but rather a combination of two other wars — one between evolutionists and anti-evolutionists, with Christians on both sides, and another between militant atheists (and agnostics) and Christians, with evolutionists on both sides.

Many Christians (including conservative Protestants) opposed the law. While many Christians rejected evolution itself, Scopes’ defense attorneys had no trouble finding Christian scientists who were ready to testify both to the scientific respectability of the theory and to its compatibility with Christian doctrine. The theory of evolution was taught at some Protestant denominational colleges, including Baptist Wake Forest and Presbyterian Wooster, though it was opposed in others.

On the Catholic side, we can take the testimony of H. L. Mencken:

“In such journals as [The Commonweal], the new Catholic weekly, both sides were set forth, and the varying contentions are subjected to frank and untrammeled criticism. Canon de Dorlodot whoops for Evolution; Dr. O’Toole denounces it as nonsense. . . . [The Commonweal] itself takes no sides, but argues that Evolution ought to be taught in the schools—not as an incontrovertible fact but as a hypothesis accepted by the overwhelming majority of enlightened men. The objections to it, theological and evidential, should be noted, but not represented as unanswerable.” 4

The trial itself did not originate as a battle between Christianity and atheism. The ACLU preferred a narrow, constitutional focus and would not have chosen agnostic controversialist Clarence Darrow (in the only case that he ever did pro bono) as Scopes’s attorney, but they were not the defendant and the final choice was not theirs. Both Darrow and Bryan (who had got himself appointed as assistant to the prosecution) brought to Dayton agendas of their own. Bryan declared the case a “duel to the death” between the Bible and atheistic evolutionism;5 while Darrow declared it a struggle to “prevent[…] bigots and ignoramuses from controlling the education of the United States.” 6 But to the extent that the conflict is seen as one between Bryan and Darrow, it is not between anything and science. As historian Edward Larson put it, “[Darrow] mixed up Darwinian, Lamarckian, and mutation-theory concepts in his arguments, utilizing whichever best served his immediate rhetorical purposes.” 7

3. The New Scopes-Trial Myth: Its Source

Unfortunately, we do not have the Old Scopes-Trial Myth entirely behind us,8 but the last few years have seen the emergence of what might best be called the New Scopes-Trial Myth, the idea that the trial is, to quote a headline in the National Review Online, “an example of Christianity standing against eugenics.” 9 The claim that this “cultural frame” fits the trial was also made by Kody W. Cooper in an essay recently posted by Word-on-Fire.10 The idea that the Scopes Trial was a battle over eugenics, mistaken though it is, has its roots in three facts.

The first fact is that eugenic thought and practice was a growing problem in the 1920s. On the theoretical side, the Carnegie Institution of Washington was funding two major eugenics research organizations.11 The American Museum of Natural History had, with much fanfare including museum exhibits open to the public, hosted the Second International Congress of Eugenics in 1921. Despite some sustained scientific objections to the soundness of eugenics work, especially that being done in the United States,12 the movement achieved noticeable success in implementing its policy recommendations. By 1925, twenty-five states had passed forced sterilization laws; by 1940, seven more would follow suit.

The second fact is that George William Hunter’s Civic Biology, the state-approved textbook then in use in Dayton, in addition to including passages about evolution, made a case for the importance of eugenics.

The third fact is that Bryan was an anti-eugenicist. He mentioned eugenics as one of the deleterious consequences of the theory of evolution in his “Menace of Darwinism” and would have done so again in his closing speech at the Scopes Trial if he had been allowed to give it.13 That speech would have included two counts from his “indictment” of evolution. His “fourth indictment” was that “it discourages those who labor for the improvement of man’s condition” since “its only program for man is scientific breeding.” 14 His fifth is that the evolutionary hypothesis would, for reasons elaborated below, “eliminate love and carry man back to a struggle of tooth and claw.” 15

4. The New Scopes-Trial Myth: A Critique

Facts those three may be, but evidence for the thesis in question they are not. The first step towards recognition of the myth-mongers’ error is to be clear about the logical relation between evolution and eugenics.

Bryan speaks as though the permissibility of eugenics were a logical consequence of accepting evolution as an explanation of the origin of new species. If that were so, then of course an argument against the permissibility of eugenics would count against the truth of the theory of evolution. But it cannot be so, for a reason that Bryan himself articulated in the text of his intended closing speech: “Science … is not a teacher of morals.” 16

Eugenics had its roots not in Darwin’s theory of the evolutionary origin of species, but in the efficacy of animal breeding (i.e., of artificial selection). Although both evolution and animal breeding had deeper roots in heredity and, when it was developed, genetics, the efficacy of the breeding practices did not depend on any theory of the origin of species.

Bryan’s claim that Darwin supported eugenicism was based precisely on Darwin’s comments about animal breeding. Bryan launched his “fifth indictment” by quoting Darwin, who wrote,

“No one who has attended to the breeding of domestic animals will doubt that [allowing “the weak members of civilized society propagate their kind”] must be highly injurious to the race of man. It is surprising how soon a want of care, or care wrongly directed, leads to the degeneration of a domestic race; but, excepting in the case of man himself, hardly anyone is so ignorant as to allow his worst animals to breed.” 17

There’s no connection to the origin of species there. The efficacy of animal breeding is also all that Hunter’s textbook had used in its case for eugenics: “If the stock of domesticated animals can be improved, it is not unfair to ask if the health and vigor of the future generations of men and women on the earth might not be improved by applying to them the laws of selection.” 18

Of course, both Darwin and Hunter would have done well to be a little more skeptical of the comparison between animal breeding and eugenics. It is weak on two points.

First, however much pigeon-breeders might deplore the seemingly deleterious effects of the promiscuous interbreeding of the pigeons in their dovecotes, it is doubtful that the feral pigeons on the Piazza San Marco and at Trafalgar Square would share the breeders’ views about what is injurious to their race and what is not.

Second, though very modest lessons from animal-breeding might be put to human use (e.g., in support of genetic screening for conditions like Tay-Sachs disease, hemophilia, and sickle-cell anemia), Darwin’s fears about the injurious effects of asylums, poor-laws, and smallpox vaccination on the human race are surely exaggerated.

Even if the claims about injuriousness were sound, getting from the descriptive claim of injuriousness to the prescriptive claim about the wisdom of eugenics (forced sterilization and marriage restrictions)19 requires acceptance of a moral principle that no evolutionist was under any logical obligation to accept. Darwin himself recognized, as Bryan did not, that the objectionable eugenic practices that Bryan feared and warned about were not logical consequences of the scientific principles of heredity that underlay both animal breeding and the Darwinian theory of the origin of species. Rather, they were the consequences of the use of those scientific principles in combination with a moral principle (utility, with a focus on possible long-range benefits) that Darwin, no less than Bryan, rejected. Having asserted that practices that allow the weak to propagate their kind are “highly injurious to the race of man,” Darwin had gone on to insist that we should respond to “the noblest part of our nature”: “if we were intentionally to neglect the weak and helpless, it could only be for a contingent benefit, with a certain and great present evil.” 20 The moral principle that Darwin deployed against eugenics he called “sympathy.” It would seem to be, if not equivalent to Bryan’s principle of love, at least equally effective in protecting the weak against the abuses that both feared.

While it is true that a belief in a logical connection between Darwin’s theory of the origin of species and eugenics could have motivated someone to go to Dayton, no matter how logically imperfect that belief might have been, other facts tell rather decisively against the New Myth.

First, Bryan embedded his complaints about eugenics (and as a minor theme at that) into his campaign against evolution, not vice versa. In one lecture, he said, “The greatest enemy of the Bible … today is the believer in the Darwinian hypothesis that man is a lineal descendant of the lower animals. Atheists, Agnostics and Higher Critics begin with Evolution: they build on that.” 21 He devoted an entire other lecture to “The Menace of Darwinism.” However much Bryan might have tried to connect eugenics and evolution, his school-laws campaign was focused on evolution. It was that, and not eugenics, that was prohibited by the model legislation he had proposed. So unimportant is eugenics to the larger story that three of the leading biographies of Bryan, while they may mention eugenics in the text, do not even include the term in the index.22

Second, the Butler Act did not forbid the teaching of eugenics. It was not even mentioned at the trial.23 Moreover, prohibiting the teaching of evolution, as the Butler Act did, would not have indirectly prevented the teaching of eugenics. One can see this from the fact that Hunter’s textbook had based the case for eugenics on animal breeding, not on evolution. About a month before the trial, but after passage of the Butler Act, Tennessee schools replaced Hunter’s Civic Biology, which was already eleven years old and thus had already reached its read-by date, with James Peabody and Arthur Hunt’s Biology and Human Welfare.24 Like Hunter, Peabody and Hunt had spent a couple of pages on eugenics, which they called “a great movement of the present day.” Although they were more temperate in their language than Hunter had been,25 they did endorse “cooperat[ion] with clergymen and others who refuse to join [the feeble-minded] in marriage.” 26 Eugenics retained its place in Tennessee’s schools.

Third, if one wants to find a really scathing critique of the eugenics practices of the 1920s in the work of one of the principals at the trial, one will look to Bryan in vain. One must look rather to the (amateur) evolutionist who wrote “The Eugenics Cult” in 1926 — Clarence Darrow! “Amongst the schemes for remolding society, [eugenics] is the most senseless and impudent that has ever been put forward by irresponsible fanatics to plague a long-suffering race.” 27 With anti-eugenicists on both the prosecution and the defense bench, it is implausible to see the trial as part of a war on eugenics.

5. Conclusion

If I were a Hegelian, perhaps I could make the two myths into a thesis and an antithesis, from which some kind of synthesis could emerge. Not being one, the best I can do by way of a conclusion is to see them as distortion and anti-, or perhaps better, counter-distortion, something that not even a Hegelian could love. While it is true that the Scopes Trial is mis-presented in the service of bad historiography, a new myth, however well-intentioned it may be, is not the appropriate correction. The conflict in Dayton was no more between Christianity and eugenics than it was between Christianity and science; it was just between evolutionism and anti-evolutionism.

[KENNETH W. KEMP is emeritus Professor of Philosophy at the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul, Minnesota. He is the author of The Origins of Catholic Evolutionism, 1831 to 1950 (CUA Press, 2025) and The War That Never Was (Cascade, 2020).]

References.

- Joseph Wood Krutch, “Monkey Trial,” Commentary 43/5 (May 1967) 83–84.

- Lawrence in an interview with Jonathan Mandell, “Inherit the Controversy,” Newsday, 17 March 1996, p. 10.

- Kemp, The War That Never Was (Cascade, 2020), ch. 5.

- Mencken, “The Tennessee Circus,” 17. Mencken had called the magazine The Conservator, but that was a mistake.

- “Bryan in Dayton, Calls Scopes Trial Duel to the Death,” New York Times, 8 July 1925, p. 8.

- Rhea County Court, World’s Most Famous Court Trial (National Book Company, 1925), 299.

- Larson, Summer for the Gods (Basic Books, 1997), 72.

- In a recent guest essay in the New York Times, Bryan-biographer Michael Kazin called the trial, less sweepingly, “a momentous clash between modern science and traditional Christianity” (“This ‘Trial of the Century’ Has Lessons for the Democrats,” New York Times, 10 July 2025, p. 22), but this is still too broad. Are Catholics, who mostly looked at the trial askance, not part of “traditional Christianity”?

- Joseph Loconte, “A Forgotten Lesson of the Scopes ‘Monkey Trial’,” National Review 3 August 2025. Authors generally do not, to be sure, write their headlines, though in this case the headline fits the story.

- Cooper, “The Scopes Trial and the Drama of Harmonizing Faith and Reason,” wordonfire.org, 1 July 2025.

- The Station for Experimental Evolution and the Eugenics Record Office.

- Garland E. Allen, “Eugenics and Modern Biology: Critiques of Eugenics, 1910–1945,” Annals of Human Genetics (2011), 75: 3: 314–25.

- The defense and the state having agreed that the jury should return a guilty verdict (Rhea County, Court Trial 311), there was no need for any closing statement from the prosecution.

- Bryan, “Text of Bryan’s Proposed Address in Scopes Case,” in World’s Most Famous Court Trial, 333. Some eugenicists did complain that others exaggerated what eugenics could do, but Bryan’s complaint is also an exaggeration. Hunter’s textbook, for example, had a three-point program: “[The] improvement of the future race has a number of factors in which we as individuals may play a part. These are personal hygiene, selection of healthy mates, and the betterment of the environment.”

- Bryan, “Proposed Address,” 335.

- Bryan, “Proposed Address,” 338.

- Darwin, Descent of Man, 134.

- Hunter, Civic Biology, 261.

- I focus here on American practice. Whether the subsequent murderous practices of Nazi Germany were even motivated by anything like eugenic concerns for the long-term well-being of the human race or were merely covered with eugenic slogans I leave for other historians to address.

- Darwin, Descent of Man, 134.

- Bryan, The Bible and its Enemies, 3d ed. (The Bible Institute Colportage Association of Chicago, 1921), 19.

- Paolo Coletta, William Jennings Bryan (Nebraska, 1964); Michael Kazin, A Godly Hero (Knopf , 2006); and Lawrence Levine, Defender of the Faith (Oxford, 1965).

- Though Bryan would have mentioned it in his summation speech, as noted above.

- Peabody and Hunt, Biology and Human Welfare (Macmillan, 1925).

- No reference there to “the feeble-minded as true parasites” and no suggestion that “if [they] were lower animals, we would probably kill them off to prevent them from spreading” (as in Hunter, Civic Biology, 263).

- Peabody and Hunt, Biology and Human Welfare, 546.

- Darrow, “The Eugenics Cult,” American Mercury (1926), 8: 129–137, at 135.